Smuggled Coins Prevent Study

Rising patrimony claims and seizures are putting ancient coin collectors and museums on alert, as recent cases highlight the risks of undocumented provenance.

Coin collectors and museums are growing increasingly concerned about potential seizures of their coins. Such could happen if a country from which the coins are attributed declares them to be part of that nation’s patrimony or that the coins have been illegally exported.

Should the coins have been sold before the date when the patrimony claims began, there shouldn’t be a problem keeping them, whereas those obtained later may have an ownership paper trail. If the coins had been illegally exported, ownership would be jeopardized.

Just how widespread coin smuggling is can’t be measured, but occasionally there is a hint at the scope of the problem. A recent seizure of ancient Punic coins is a good illustration of how vulnerable ancient coins are to trafficking.

In March 2022, an individual was arrested in Norway for illegally importing 30 Punic bronze coins. Due to diplomatic “engagement,” smuggling charges were dropped; however, the coins were returned to Tunisia, from which they allegedly originated. A study of these coins was recently published in the journal Libyan Studies by Professor Håkon Roland and Dr. Paolo Visonà.

The seizure came following a coin dealer becoming suspicious of the coins. The seller had provided the coin dealer with photographs and videos showing large quantities of corroded coins being loaded into a van, but with no further explanation.

Oslo Police were notified, who in turn requested assistance from the Museum of Cultural History at the University of Oslo. This was followed by Norway’s Ministry of Culture and Equality coordinating its repatriation to Tunisia.

What becomes frustrating to law enforcement, researchers, and collectors alike is that the individual arrested for trying to sell the coins never provided specifics about where he got them or whether this was part of a larger hoard. According to Roland and Visonà, the coins appear to have originated from either a shipwreck or from some submerged coastal structure.

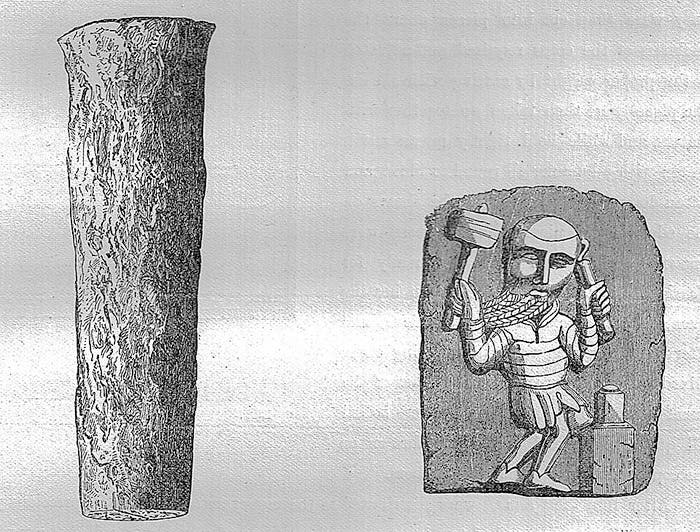

The collection consisted of 24 larger- and six smaller-diameter coins, each featuring the goddess Tanit on the obverse and a horse before a palm tree on the reverse. Tanit’s hairstyle matches that of Second Punic War-period coins, likely struck at the same Carthaginian mint. Coins of these types appear to have circulated until about 205 B.C. Following the war, only poor-quality coins were issued, intended to finance the military.

Similar coins excavated properly in an archaeological context elsewhere indicate that they circulated widely throughout North Africa. Significantly fewer examples have been found in Europe, primarily in Croatia, Dalmatia, and Menorca. The coins are not rare, but the historical background of the 30 recently seized coins has been lost due to smuggling.

According to Roland, “The spike in sales of Carthaginian and other coins (specifically, Illyrian coins, e.g. of Ballaios) since the 1980s can be attributed to multiple interrelated factors, including regime changes, the unregulated and increased use of metal detectors, lack of ad hoc legislation, increased opportunities for criminal activities due to open borders across multiple European countries, and corruption at various levels of law enforcement agencies in areas of Europe and North Africa.”

He added, “Provenance information for objects offered for sale is often incomplete or fabricated, and it can be extremely difficult to distinguish between legal and illicit artifacts. Private individuals who wish to purchase an object should ask themselves where it originally comes from, whether it is subject to export restrictions in the country of origin, and, if so, whether an export permit exists.”

You may also like: