Short snorter find bears royal sigs

By Mark Hotz For this month, I am going to vary from the normal format of “Notes on National Banks” and bring to you what I think is a very…

By Mark Hotz

For this month, I am going to vary from the normal format of “Notes on National Banks” and bring to you what I think is a very historically interesting piece of paper money that I recently picked up. I hope you will enjoy the story.

A couple months back, I was at a small club coin show in central Pennsylvania. There really wasn’t much to buy, as I had seen many of the same dealers the past month at another local show. As I perused the offerings, I came across one fellow who had mostly U.S. coins, but did have a very small box with some foreign paper money. So I flipped through it.

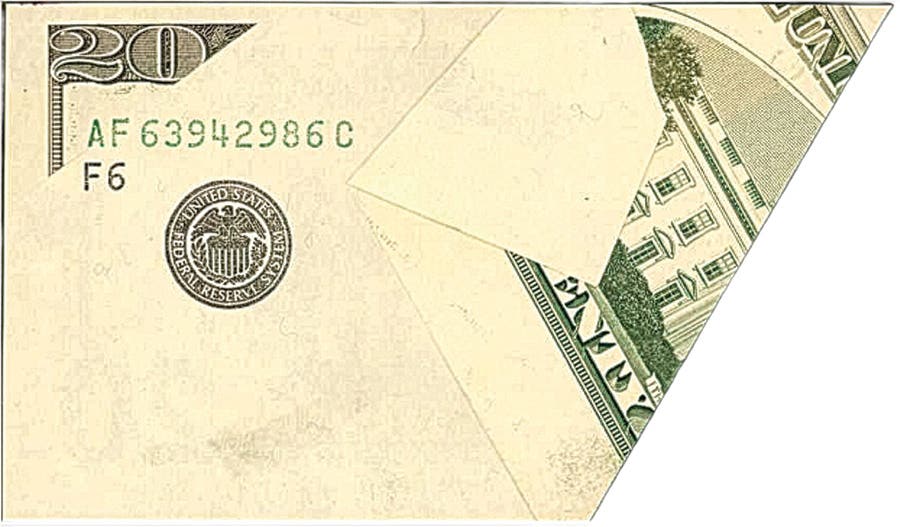

There really wasn’t much of interest in the box, and what was there was priced at full catalog value. But I did espy a very common piece of Allied Military Currency issued for use by U.S. troops in France during World War II. It was a small square 10-franc note, one of the lowest denominations. Normally, I wouldn’t even give such an item a moment’s notice, but this one had some signatures on it, and I like signed notes of the period.

The dealer had labeled it a “short snorter,” a term that has come to encompass any World War II-era note that has a lot of signatures on it, usually of U.S. and/or foreign soldiers. The original idea of the “short snorter” had to do with crossing the international dateline (and thus shorting a day) or just acquiring signatures of everyone on a particular military flight. However, it seems as if just about everyone was signing currency during World War II, so the term has come to cover all signed notes.

On the face of it, the note had two signatures that I could not make out at all, and I am pretty good at reading old style cursive. I flipped it over and a few more were on the back. In the bottom margin, I used a magnifying glass to read what appeared to say “Aspasia, Princess of Greece.” I know a good deal about European royalty, but I had never heard of any “Aspasia.” Just the same, the asking price was very modest, so I bought it.

When I got home, I examined the note further. Two signatures on the back center were illegible to me—I believe they are not in English. Along the left margin, the signature “Alexandra R” underlined was easily readable. Regular people do not put “R” after their signatures—that letter normally signifies royalty, either for Regina (queen) or Rex (king). This was beginning to look good.

I immediately went online and here is what I found out. Aspasia was Aspasia Monos, a Greek commoner who became the wife of Alexander I, king of the Greeks, daughter of Col. Petros Manos, aide of King Constantine I of Greece, Aspasia grew close to the royal family. After the divorce of her parents, she was sent to study in Switzerland. She returned to Greece in 1915 and met Prince Alexander, with whom she became secretly engaged to, due to the expected refusal of the royal family to recognize the relationship of Alexander I with a woman who didn’t belong to one of the European ruling dynasties.

Greece’s difficult position during World War I caused the abdication of King Constantine and Alexander became king in 1917. He secretly married Aspasia on Nov. 17, 1919. When the Greek public learned of this, a huge scandal erupted, and Aspasia was forced to leave the country. Eventually she was reunited with her husband and returned to Greece. Due to the fact that her marriage had not been approved by the Metropolitan, the head of the Greek Orthodox Church, she was not entitled to be called queen. During the summer of 1920, she became pregnant.

Things then took a turn for the worse. On Oct. 2, 1920, King Alexander was walking on the royal estate at Tatoi when the pet macaque monkey of the vine keeper got into a fight with Alexander’s dog, Fritz. When Alexander attempted to separate them, the macaque bit him. Alexander thought it nothing, but the wounds became infected, and Alexander died on Oct. 25. Now Aspasia had no title and was 4 months pregnant.

King Constantine was restored to the throne at the end of 1920. When Aspasia gave birth to a girl, Alexandra, on March 25, 1921, King Constantine and his wife, Queen Sofia, fell for the child. Since only a male could succeed to the throne of Greece, the new baby was no threat.

King Constantine eventually got the child Alexandra the title of Royal Highness Princess of Greece and Denmark. It wasn’t until the end of 1922 that he also was able to maneuver a decree giving Aspasia also the title of Princess of Greece.

Fast forward to World War II. Events in Greece had forced Aspasia and Princess Alexandra to move to Italy and then to Egypt and South Africa. In 1941, they were allowed to move to the United Kingdom, which was then hosting a variety of exiled royals from Nazi-occupied countries. They arrived in Liverpool and eventually settled in the Mayfair district of London. It was there, in 1942, that Alexandra met her third-cousin, King Peter II of Yugoslavia, at an officers’ gala. They fell for each other and considered marriage, but the objections of Peter’s mother and the Yugoslav government-in-exile prevented the marriage until 1944, when on March 20, they were married at the Yugoslav Embassy in London. Britain’s King George VI was in attendance.

Alexandra, the daughter of Princess Aspasia and King Alexander of Greece, was now Queen of Yugoslavia. She signed the note “Alexandra R” sometime in late 1944 or 1945.

But there’s more. Once I learned who “Alexandra R” was, I looked carefully at the note again. On the top margin was another signature. Sure enough, it was her husband, who signed “Peter II R” as King Peter II of Yugoslavia. Peter had become the boy-king of Yugoslavia in 1934 when his father, King Alexander of Yugoslavia, was assassinated during a visit to Marseille, France. In 1941, Peter was forced to flee Yugoslavia when it was invaded by the Nazis, and ended up, along with his government-in-exile, in London where he met Alexandra.

The king completed his education at Cambridge University before being commissioned in the Royal Air Force. In 1942, he made an ambassadorial visit to America and Canada, where he met American President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon MacKenzie King. The whirlwind tour was unsuccessful in securing Allied support for the exiled Yugoslav monarchist cause. Roosevelt and Churchill had already engaged the support of the Communist Yugoslav Government in the Allied effort to defeat Nazi Germany. with a view to ending the hostilities.

Peter and Alexandra never returned to Yugoslavia. When the war ended, the Yugoslav Communist Constituent Assembly deposed him and abolished the monarchy. He settled in the United States and died in 1970. Queen Alexandra died in 1993 in the United Kingdom. Princess Aspasia, Alexandra’s mother, died in 1972 in Italy.

How did these three notables end up signing this simple piece of Allied Military Currency? Most likely in London, but for whom I will never know. Somehow, it ended up in the United States only to be discovered in a “junk” box decades later. Several other signatures grace the note, but I can’t make them out—several appear to be in Cyrillic. If any of my readers can make out a signature or has a good guess, please let me know. I have included photos of both sides of the note as well as photos of the personalities involved.

Readers may address questions or comments about this article or National Bank Notes in general to Mark Hotz directly by email at markbhotz@aol.com.

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• Order the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, General Issues to learn about circulating paper money from 14th century China to the mid 20th century.

• With nearly 24,000 listings and over 14,000 illustrations, the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, Modern Issues is your go-to guide for modern bank notes.