Hotz off the Press: A Monumental Time in Sipesville, PA

A rare bank note drew Mark Hotz to Sipesville, Pennsylvania—where small-town banking history meets moments of national remembrance.

When considering this month’s article, I wanted to revisit an interesting town with recent historical significance. Accordingly, let’s visit sleepy Sipesville, Pennsylvania, a rural burg tucked away in bucolic Somerset County that is more of a hamlet than a town. Little happens in this part of rural Pennsylvania, but that all changed over the course of two decades, in the span of several months.

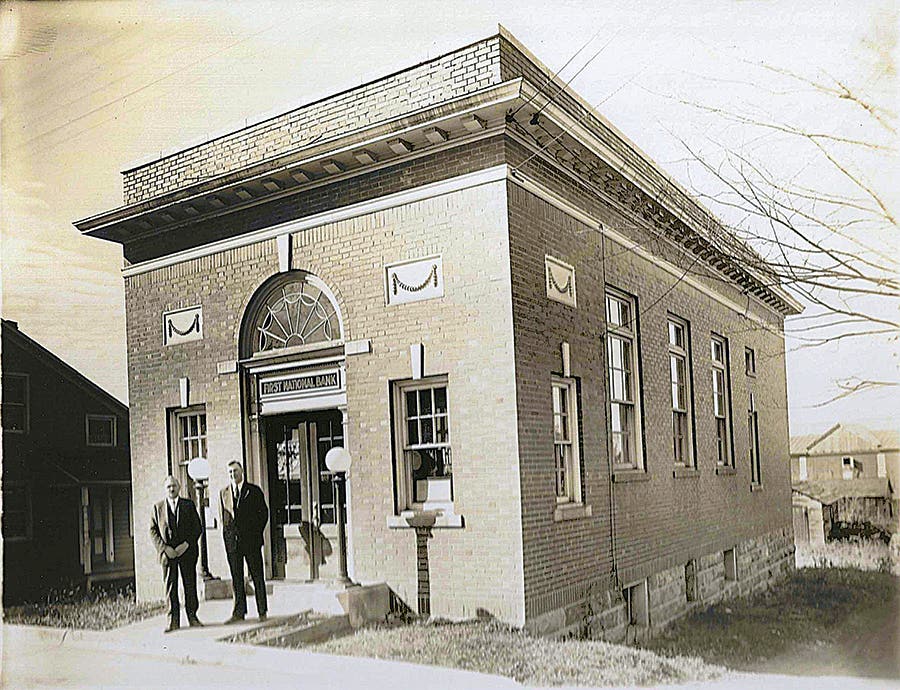

My interest in Sipesville came haphazardly, just like many of the towns featured in this column, when I chanced upon the opportunity to purchase a wonderful vintage 6” x 8” photograph of the First National Bank of Sipesville, charter #11849. The photograph shows the classic small-town bank building from 1930, with the bank officers, Park L. Hoffman, cashier, and Pierce Miller, assistant cashier, standing proudly out front. The photograph was so appealing, and it now hangs smartly framed on my office wall.

On a trip to the Pittsburgh area not long ago, I decided to take a detour off the Pennsylvania Turnpike and hike up to Sipesville to see if the old bank building remained. I imagined that it would, given that such a fancy and well-built structure would be a valuable commodity in a tiny town.

State Route 601 curves northward from Somerset, the county seat, and winds through a rolling, forested landscape on the way to the town. About eight miles north, a fork to the right indicates “Sipesville.” The city itself slowly spread out before me, little more than a series of period houses straddling each side of the road. As I continued along, straining to look at both sides of the street at the same time, I came upon the U.S. post office and a familiar sight. It was the old First National Bank.

The First National Bank of Sipesville was a very small financial institution. Chartered in 1920, with a tiny capital of just $25,000, the bank issued what I like to call “pocket change” circulation: just over 2,000 sheets of large-size notes, and a few hundred sheets of small notes, including a paltry type 2 issue consisting of just 63 notes! The bank left just $12,500 outstanding in 1935, of which a mere $250 was in large-size notes. It is hard to imagine why a town like Sipesville, with a population of less than one hundred in 1929, needed a national bank (although I have since seen many instances of this, including Dry Run, Pennsylvania).

It is a very rare bank today, with just a single large and 3 small notes reported. In 2014, Heritage Auctions offered a small-size note in its FUN Auction; prior to that, the last public offering of a Sipesville note was in a 1981 Hickman & Oakes sale. Heritage Auctions recently offered the lone known Sipesville large-size note, which I purchased. It bears the pen signatures of Park L. Hoffman, cashier, and the stamped signature of C.B. Korus, president. On the small note, Pierce Miller is now cashier.

I had brought along my photo (still in its frame) so that I could take a modern photograph from the same vantage point. The building was remarkably little changed from the 1930 view. The addition of a canopy over the entrance, a handicapped ramp, and a small shed seemed to be the only physical changes. The addition of a familiar blue mailbox gave the scene an incongruous look.

Only when I parked my car and got out to take some photos did I notice other, subtle changes. The roof overhang visible in the 1930 photograph is now gone, and, oddly, some of the windows on the right side of the building have been altered. Amazingly, the same structures visible to the left and behind the bank in the 1930 image are still standing today!

I went into the building, now serving as the Sipesville post office, and explained to the postmistress my interest in the old bank. She showed me the old vault still inside and pointed out an article from the local paper that gave some reminiscences about the town. One interesting comment concerned the bank: when it was taken over by the Somerset Trust Co. in 1936 and closed, an armored car from Somerset arrived in the middle of the night to empty the vaults and remove all the cash.

It was while perusing the newspaper articles posted on the wall that I began to learn of Sipesville’s modern notoriety. I had not realized it before coming to the area, but Sipesville had been in the national forefront not once, but twice recently! Sipesville is the nearest town to the Quecreek Coal Mine, where nine Pennsylvania miners had been trapped 240 feet below the surface on July 24, 2002. The men accidentally drilled into the nearby abandoned Saxman Mine and released 50 million gallons of water into their own shaft, cutting them off from the surface. The men were trapped in a small chamber just over 4 feet high and 18 feet wide, in frigid 55-degree water. The saga of the trapped miners and their eventual rescue four days later unfolded on national television. A monument to the men and their rescuers stands in front of the Sipesville Fire & Rescue Co.

Only a few months after the Quecreek Mine accident came the largest tragedy ever to hit Somerset County: the crash of United Airlines Flight 93 into a field near Shanksville, Pennsylvania, on September 11, 2001. The flight, hijacked by 9/11 terrorists, was believed to be heading for the White House when the passengers decided to take matters into their own hands and attacked the terrorists, causing the plane to crash near Shanksville, a small town just 10 miles southeast of Sipesville.

I ventured tentatively south from Sipesville towards Shanksville, following directions given to me by the postmistress, to see the Flight 93 site. Shanksville itself is not easy to find and seems totally out of place in the middle of nowhere. As a result of increased numbers of visitors, the town maintains directional signs that travelers can follow to the Flight 93 crash site, now a national memorial, a solemn tribute to the heroic actions of the 40 passengers and crew members aboard United Airlines Flight 93 on September 11, 2001. Spanning 2,200 acres of a reclaimed strip-mine site, the memorial’s design is intended to foster quiet reflection and honor the sacrifice of those who prevented a terrorist attack on the U.S. Capitol.

Key features of the site, which the National Park Service manages, include the Tower of Voices, a 93-foot-tall, monumental musical instrument with 40 wind chimes, and the Memorial Plaza, which leads visitors along the boundary of the crash site. The crash site itself, the final resting place of the victims, is a hallowed, restricted area marked by a large 17-ton sandstone boulder at the point of impact.

The Wall of Names is a central element of the Memorial Plaza, located along the precise trajectory of the flight’s final moments. It is composed of 40 individually selected and polished white marble panels, each 8 feet tall, inscribed with the name of a passenger or crew member. The wall appears as a solid, unified structure from a distance, symbolizing the collective action taken by the individuals on board. At the same time, a small space between each panel highlights their unique individuality. A Ceremonial Gate, constructed of hewn hemlock beams with 40 cut angles, separates the public plaza from the sacred crash site and is only opened for family members on September 11 each year.

Since it was a weekday, there were only a few visitors at the memorial. I was totally amazed at how the weather had changed, as if to reflect the nefarious nature of the incident itself. What had been a reasonably sunny day was now completely overcast, cold, and blustery, with strong winds and occasional large droplets of rain. The whole site was masked in the pallor of gloom, and I could sense the enormity of the tragedy that had taken place there. I have included photos of the memorial, gleaned from the U.S. Park Service website.

My visit to Sipesville, ostensibly just to see and photograph the old bank, had turned into a real learning experience. I had smelled the coal dust in the air and saw the area of the coal mine rescue that had gripped the nation. I had ventured to the site of one of the 9/11 events and had been awed by the experience. Exploring towns for national banks can have interesting collateral effects!

You may also like: