Marveling over unconventional notes

by Mark Hotz Last month, I concluded my multi-part series on inscribed currency, including notes from the Civil War, Spanish American War, World War I, and the ubiquitous short snorters…

by Mark Hotz

Last month, I concluded my multi-part series on inscribed currency, including notes from the Civil War, Spanish American War, World War I, and the ubiquitous short snorters of World War II. The last installment included miscellany. For this month, I am including a potpourri of oddball notes that round out my collection. I am interested in any sort of currency that tells a story either about what it was used for or where it has been.

Next month, we will revert to the Hotz Off the Press – Notes on National Banks, which I know many of you enjoy and await.

Our first item is a seemingly ordinary Series of 1928 $1 Silver Certificate. I bought this note way back when from dealer David Koble for $20 because it had been all the way to New Zealand and back. Affixed to the back of the note was a New Zealand orange 2-pence postage stamp, with a “cancellation” from the National Bank of New Zealand, Ltd. dated Dec. 12, 1931. The face of the note had a far more faded bank stamp indicating that the note had been accepted at the bank branch in Palmerston North, New Zealand. I was fascinated at the time as to how this note got to New Zealand during the Depression and why it had a postage stamp applied. In any event, it somehow made it back to the United States, and I have had it for many years.

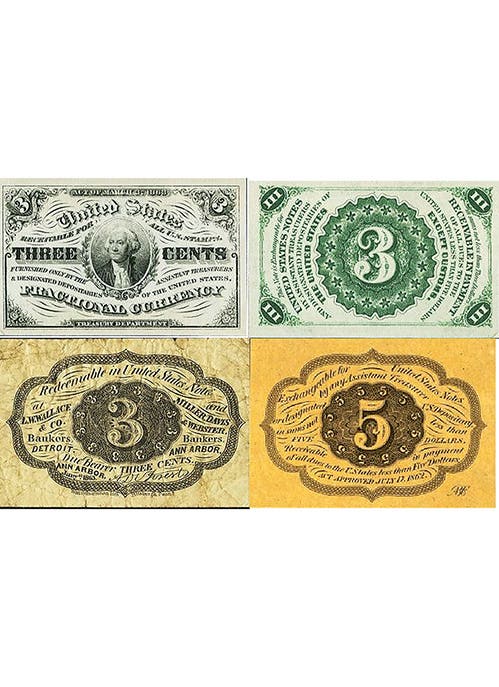

The second item is a rather tattered 50-cent Fractional Currency note, Fourth Issue, with portrait of Edwin Stanton (Fr. 1376). The note has been pasted to a large calling card of Clacius & Co. Apothecaries and Chemists, 322 West Madison St., Chicago. Inscribed below the note in a neat pen script is, “1st Door Spring Sold July 13, 1874/ Sold to Thompson.” I was quite intrigued when I found this, because I found it odd that the apothecary shop would commemorate the first door spring sold. But the main point is that as a normal well worn out 50c Stanton fractional, the note would have little interest. But knowing where it was and what it was spent for on July 13, 1874, gives me the time and place information that makes all of this so interesting.

Our third note is a nondescript Series of 1923 $1 Silver Certificate, easily the most common large-size note available to collectors. I normally don’t even buy these. But this well-used note was torn way back when and was repaired with a piece of colored paper advertising Curtiss’ BABY RUTH Peppermint Gum, “The FLAVOR sticks.” Curtiss Candy Company was famous for its Baby Ruth candy bar, still sold today, and when it introduced the bar in the 1920s, baseball star Babe Ruth sued them for using his name. The candy company had named the bar for Baby Ruth Cleveland, the daughter of the late president. This really made no sense, since Ruth had been born in 1891 and had passed away long before the candy bar came out. But in 1931, a U.S. Patent Court sided with the Curtiss Company against Babe Ruth. The Curtiss Co. also made varieties of chewing gum, including the peppermint gum that was introduced in the 1920s.

Our fourth note is a rather common Fractional Currency 10-cent note of the Series of 1874 (Fifth Issue). These are among the most common of all fractional currency notes. It features a portrait of William Meredith, Secretary of the Treasury in 1849. For whatever reason, people in the late 19th century felt the need to alter the portrait of Meredith to resemble various and sundry other people. I have seen many of these, ranging from the Pope to Otto von Bismarck! The illustrated note has Meredith transformed, in full color, into a Native American, complete with face paint.

Our fifth note is a Series of 1914 $20 Federal Reserve Note, Boston District (Fr. 967). This is not a particularly scarce type note, but I bought it because it had been apparently deposited in a bank in 1950 – long after the demise of large-size notes. It has a large blank rubber stamp from the New Bedford (Mass.) Institution for Savings, North Branch, indicating that the note was received March 21, 1950, and sent on with checks for redemption. It was interesting to me to see how late large-size notes were still being turned into banks.

Our last note for this article is a Series of 1935-A $1 Silver Certificate, in what looks to be extremely fine condition, housed within a cellophane advertising slip. On both sides of the clear slip is advertising for the Carstens Packing Company. The face reads, “I AM A Carstens PAYROLL DOLLAR. Many more like me are paid to and circulated in this locality each week by employees of Carstens Packing Co. Every industry, business and individual benefits. Please keep me in this envelope.”

The back has a similar message: “CARSTENS PACKING CO. PAYROLL DOLLARS ‘ROLL’ into thousands of pockets. Your purchases of CARSTENS QUALITY PRODUCTS means more work for more people.”

The Carstens Packing Company was the largest meat-packing company on the West Cost of the USA. Plants were located in Tacoma, Seattle & Spokane, Wash. They packaged beef, ham, sausage, lamb, pork, veal and other meat products. In the 1930s, they served 2,000 stores in the West. The Carstens Company main plant was located in Tacoma. The company existed into the mid 1950s, when it was sold to Hygrade Food Products.

Readers may address questions or comments about this article to Mark Hotz directly by email at markbhotz@aol.com.

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• Order the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, General Issues to learn about circulating paper money from 14th century China to the mid 20th century.

• When it comes to specialized world paper money issues, nothing can top the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, Specialized Issues.