Around the World: Coin Inscriptions Suggest Ethnic Roots

Newly unearthed coins from Uzbekistan challenge long-held views of early Turkic identity, sovereignty, and statecraft—revealing the earliest known use of the term “Turk-Kagan.”

It can be argued that coins not only represent history but also serve as a document of it. A recent discovery in the Fergana region in modern Uzbekistan of perhaps 20 coins (the exact number was not verifiable at the time this article was written) that share stylistic traits and inscriptions of significance compared to previously known coins from Tashkent is now challenging the early Turkic identity, the legitimacy of early khagans, and the sophistication of pre-Islamic Central Asian politics.

Khagan is a Mongolian and Turkic imperial title, generally regarded as equivalent to that of an emperor. Khagan can be translated to mean “khan of khans.” Turkic people is a catchall description of Asian, Caucasus, Central Asian, Eastern European, and parts of the Middle East ethnic groups that share common linguistic roots within the greater Turkic family.

It is generally accepted that the First Turkic Khaganate was a sixth- to eighth-century nomadic empire stretching from northeast China to the Black Sea. This khanate was the first of several dynasties that shaped the culture, physical location, and dominant beliefs of the Turkic peoples.

The Fergana Valley is approximately 300 kilometers, or about 185 miles, east of Tashkent, the capital of Uzbekistan. Archaeological excavations of the Greater Fergana Canal have uncovered monuments dating as far back as being from the Bronze Age. The Fergana-Syrdarya Corridor of the Silk Road was an important link between China and the Byzantine Empire. In 568, Byzantine Emperor Justin II formed an alliance with the First Turkic Khanate ruler Istami I, through which Byzantine merchants could purchase Chinese silk without interference from the bordering Sasanian Empire.

Some historians theorize that the Ashina clan, which ruled the First Turkic Khanate, had non-Turkic names and later became “Turkicized.” This theory is now being challenged by Professor Gaybulla Boboyorov of the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, a renowned Turkologist historian, based on his study of the epigraphic evidence on the coins found at Fergana.

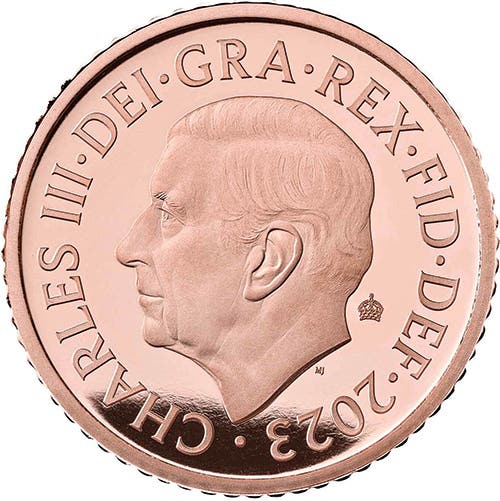

According to Boboyorov, a study of a 40-millimeter-diameter bronze coin attributed to Tashkent, dating from the late 6th or early 7th century, featured the Sogdian inscription “TWRK X’Y’N,” which translates to “Turk-Kagan,” a term previously unknown on coins from that period. The obverse depicts a man with slanted eyes, a thin mustache, and long hair. The reverse features the Turkic clan symbol, the tamga, and an inscription. The coin has been known for over 20 years and is featured in Boboyorov’s 2007 catalog, “Coins of the Göktürk Khanate.”

Other contemporary coin types associated with Tashkent feature enthroned or equestrian-related portraits of rulers accompanied by crescent moons with eight-pointed stars. The coins have titles including “Cabgu (Yabgu),” “Cabgu-Kagan,” and “Kagan.” The iconography predates Islamic control of Central Asia by between 150 and 200 years.

Some of the coins recently discovered in Fergana depict rulers on wolf-shaped thrones, accompanied by inscriptions resembling the Old Turkic-Runic script. Wolves were sacred animals in Turkic mythology. The titles indicate what Boboyorov describes as “a deepening political structure and a desire to project sovereignty.” One coin has the Sogdian phrase “Cabgu Turk-Kagan,” accompanied by Brahmi and Old Turkic-Runic inscriptions. Sogdian is an eastern Iranian language. Similar Brahmi script inscriptions have been found at the Turkic Bugut and Khoshoo-Tsaidam archaeological sites in Mongolia.

Coins in the Fergana find with the legend “Turk-Kagin” predate Orkhon inscriptions by more than 150 years. The Orkhon inscriptions are bilingual texts written in both Middle Chinese and Old Turkic, utilizing the Old Turkic alphabet. The inscriptions on these coins are now the earliest known use of “Turk” and “Turk-Kagan,” which proves they were used during the late sixth and early seventh centuries. The coins, according to Boboyorov, show a progression of the royal titles from Yabgu to Yabgu-Kagan and then to Kagan. The professor said this mirrors the historical shift following the conquest of the Eastern Göktürks by the Chinese Tang dynasty.

Boboyorov stated that the division of the Göktürk Khaganate into Eastern and Western branches is supported by coin evidence, which reflects the legitimacy and institutional traditions of early Turkic statehood. Boboyorov said, “These coins refute the long-standing belief that the Göktürks were merely nomads who didn’t engage in minting or economic systems.”

He continued, “I am a historian, not an archaeologist, but sadly, our archaeologists have not shown enough interest. Dozens of early urban sites from the Göktürk era remain unexplored in Uzbekistan.”

You may also like: