Knox-signed New Ulm note found

By R. Shawn Hewitt For me, Christmas has arrived early this year. In late October, I acquired a very special Minnesota obsolete bank note—one that was fabled and virtually foretold…

By R. Shawn Hewitt

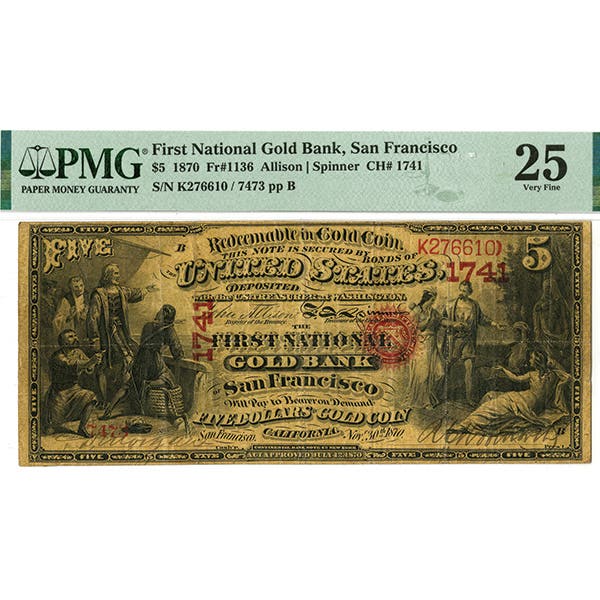

For me, Christmas has arrived early this year. In late October, I acquired a very special Minnesota obsolete bank note—one that was fabled and virtually foretold by prophecy. It is a $1 note from the Central Bank of New Ulm, Minn., bearing the autograph signatures of H.M. and J. Jay Knox. The rarity, which is in a remarkable and original state of preservation, was found belonging to a rural Minnesota family that held this note and others for generations.

This design is the only one from Minnesota with a Santa Claus vignette, described by vignette authority Roger Durand as a Type III Santa. It was issued in 155 years ago in 1861.

This note was accompanied by other Minnesota notes and those of several East coast states. A common theme of this grouping is that most of them were either counterfeits, or notes of banks that failed. That is, they could not be redeemed for full face value in coin. The Central Bank was one of those failed banks. This suggests that they belonged at one time to a banker or merchant who encountered them during his business, but could not pass them on.

In my 2006 publication, A History & Catalog of Minnesota Obsolete Bank Notes & Scrip, I include a detailed history of the Central Bank, which discusses the fact that this bank was acquired by brothers Henry and John Jay Knox in 1860. The name John J. Knox will be familiar with collectors of National Bank Notes.

Knox (1828-1892) grew up in Oneida County, N.Y. in the 1830s and 1840s. He was the namesake of his father, who was a successful merchant and banker. Knox earned a degree at Hamilton College in 1849 and worked at his father’s bank in Vernon, N.Y. In the late 1850s, he and his younger brother Henry moved to St. Paul, Minnesota to take advantage of the opportunities available on the western frontier. With his father’s assistance, they established J. Jay Knox and Co., and became a prominent banking house in the city.

Knox learned firsthand about the Wild West nature of banking in Minnesota Territory. The territorial government banned the issue of bank notes, but creative bankers were easily able to circumvent the laws simply by endorsing the notes of otherwise worthless out of state banks. They hand-wrote an endorsement clause on the notes, signed them, and they became money. Knox was among the bankers to issue endorsed notes.

When statehood was achieved in 1858, among the first laws of the state legislature was an act to enable free banking in the state, with the privilege to issue currency. Notes were to be backed by the new Minnesota 7s, which were obligations of newly formed railroad companies. The bonds were thinly traded and did not have a ready market, yet they were accepted at 95 percent of face value as note security. Almost as soon as bank notes backed by these bonds were issued, they were heavily discounted in trade.

Among the new banks was The Central Bank of New Ulm, a German community located about 100 miles from St. Paul. The Knox brothers purchased the bank from its organizers a few months after the bank opened. While the notes were floated in St. Paul, it is apparent that the remote location was deliberately chosen so as to reduce the likelihood that notes would be presented at the New Ulm office for redemption.

In February 1862 Knox wrote an essay that appeared in the Merchant Magazine and Commercial Review, a widely read trade publication that supported Treasury Secretary Salmon Chase’s vision of a national banking system. The article was noticed by Chase, who made Knox an offer to serve in the Treasury Department as a disbursing clerk. Knox accepted the position in 1863.

Knox’s years of service was rewarded by being appointed Comptroller of the Currency, the top official who oversaw the regulation of national banks throughout the country, in 1872. He held this position until 1884, when he returned to the private sector.

The irony in all this is that Knox owned and operated his bank under the kind of system that he decried in his writings in support of national banking—one with weak protections for note holders—and he used this to his full advantage. The Central Bank of New Ulm closed in 1862; its notes were presented for redemption, but Knox refused payment, and the state forced the bank into liquidation. The state auditor sold the bonds on deposit for a deep discount, leaving only enough hard money to pay bill holders 30 cents on the dollar for Central Bank notes.

Knox wrote his early signature as J. Jay Knox, to avoid confusion with his father’s name. The 1861 signature differs significantly in appearance compared to later known examples of his signature found 20 years hence on comptroller documents. He either had someone sign the early bills by proxy, or he altered the style of his signature as he changed it to John J. Knox. Francis Spinner’s ornate and well-recognized signature is known to have evolved over time, using different types of pen nibs to achieve his desired effect. It is possible Knox learned from his colleague in Washington.

The fact that this is a Minnesota Santa Claus note is an even bigger draw to collectors, however. The popular theme and vignette has captivated collector interest for decades, and this note is new to the census. The final sentence on p. 299 of my book states that if it was ever discovered, a “high grade $1 note on the Central Bank signed and issued by John J. Knox would be an epic obsolete bank note.” As a note of that description has remained unreported until now, the foretelling of 10 years ago has finally come to pass.

The design also features a portrait of Peter Stuyvesant, the last Dutch director-general of the colony of New Netherland, now known as New York City. His portrait is observed on other Santa Claus notes as well. The connection appears to be this, according to Wikipedia: “The tradition of Santa Claus is thought to have developed from a gift-giving celebration of the feast of Saint Nicholas on Dec. 6 each year by the settlers of New Netherland. The Dutch Sinterklaas was Americanized into ‘Santa Claus,’ a name first used in the American press in 1773…” The German heritage of New Ulm was undoubtedly a factor in the selection of these vignettes due to that nation’s long-standing ties to the Netherlands.

Discoveries like this continue to make the hobby interesting and fun. What’s the next unreported Minnesota note to be found? I think it will be an issued note on the Marine Bank of St. Paul. Only proofs are currently known, but enough were unredeemed after the note-issuing period that one is bound to turn up some day.

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• The Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money is the only annual guide that provides complete coverage of U.S. currency with today’s market prices.

• Are you a U.S. coin collector? Check out the 2017 U.S. Coin Digest for the most recent coin prices.