The Mint and Coinage in 1837

by R.W. Julian Some years in American numismatic history are more colorful than others but for the 19th century, we often think of 1873 as the most interesting. Yet 1837…

by R.W. Julian

Some years in American numismatic history are more colorful than others but for the 19th century, we often think of 1873 as the most interesting. Yet 1837 has to be regarded as even more important in the collecting world as the critical changes of that year, in the opinion of many, outweigh those of 1873.

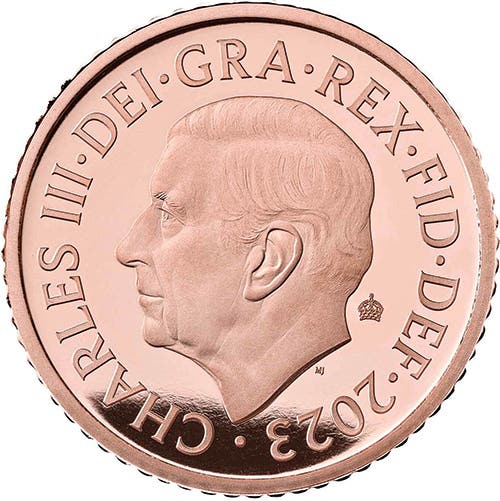

Dr. Robert M. Patterson had become mint director in early July 1835 and immediately set about making profound changes at the Philadelphia Mint, not only in the way that coins were struck but also in their artistry. The new director was determined to put American coinage on a par with the best Europe had to offer. Patterson had lived in Paris in the early 1800s and was well acquainted with the high standards of European coinage.

In March 1836 the first steam-powered coinage had taken place, forever replacing the old screw press in the striking of the large copper cents. As the months passed the smaller silver and gold coins were added to the output of the steam press. The new press did not strike all of the 1836 coins, however, the most notable exception being the lettered-edge half dollars.

Chief Coiner Adam Eckfeldt had tried to strike reeded-edge half dollars in 1836 on the new press but this was a partial failure because the press was not quite ready and there were ejection problems once the coins had been struck. As a result, only a few thousand of these special 1836 half dollars were made and today they are scarce.

The 1836 reeded-edge half dollar is especially interesting because some of the standard references, including in particular the Red Book, have incorrect entries. These special 1836 halves were coined on the old standard of 1792 (.8924 fine silver) and not the standard of 1837, (.900 fine.) This means that the 1836 reeded-edge half dollar is a must for a complete half dollar variety set, a fact not that well known among collectors.

This same reeded-edge half dollar, as well as its brother of 1837, is also rather special in that it marks the final act in a small drama that began several years earlier. Mint Director Samuel Moore, who served from 1824 to 1835, was of the opinion that E PLURIBUS UNUM did not belong on the coinage unless part of the Great Seal. He had consulted numerous people, including former President Thomas Jefferson, and came to the conclusion that this motto was nothing more than a punning way of saying UNITED STATES in Latin.

The 1836 lettered-edge half dollars were the last coins on which the old motto was used in the 1830s. Moore’s successor, Robert Patterson, was equally adamant about the superfluous motto but did agree to its use on one more occasion, in 1849 when the Great Seal was put on the reverse of the new Longacre double eagle. In February 1873 Congress, in the mistaken belief that the motto should be on the coinage, wrote it into the mint law and it remains there to this day.

Patterson was also interested in re-codifying the mint laws in order to simplify a number of technical matters. To this end Congress accommodated him by passing a comprehensive mint bill in early 1837; it was signed into law by President Andrew Jackson on Jan. 18. In particular, the gold and silver coinage, for the first time, now had the same fineness, 900/1000.

For reasons that are not entirely clear, there was then a delay of 35 days until the first precious metal coinage was delivered by the chief coiner. This seems a rather long wait even though the weights and finenesses of all silver and gold coins were slightly altered. There was no doubt there was a period of adjustment as new rules went into effect but still, the delay existed.

The first delivery of precious metal coinage under the new January 1837 rules came on Feb. 22. The date was no doubt chosen for its association with President George Washington, well known for his interest in the early mint. The coiner delivered 151,000 halves, 45,000 dimes, and 60,000 half dimes. Warrant No. 1476 was prepared by the treasurer’s office for this delivery. It all seems normal and according to regulations until some other matters are taken into consideration.

In 1836 the last silver coinage delivery, that of 600 Gobrecht dollars, was under Warrant 1473 while the gold coinage of that day (40,500 half eagles) was under 1472. Thus the warrants numbered 1474 and 1475 are missing and there is no accounting for them. (The copper coinage was on a different warrant system; all of the 1836 cents were on one warrant, No. 146.)

(A document has been discovered which appears to indicate that the Gobrecht dollars delivered on December 31 under warrant No. 1473 were actually struck the first week of January 1837. Backdating was relatively common at the Mint though whether this affected the missing warrant numbers is uncertain.)

A missing warrant number is a very strange event in the Mint accounts of any period. We are, however, also faced with the curious problem of a lengthy delay of the first coinage from the passage of the new mint law on Jan. 18.

A letter written by the Director on June 30, a few weeks later, allows us to speculate on some forces that might have caused these circumstances to arise. Dr. Patterson noted in a letter to the Treasury that there had been frequent interruptions to the steam coining apparatus because of mechanical problems.

It may well be that these problems were connected with the ejection of the coins from the collar that reeded the edge. When a coin is struck in a close collar, the pressure of the dies on the faces of the coin forces the metal to expand outwards towards the grooves of the reeded collar. Perhaps the collars proved difficult to manufacture to precise specifications and the coins would not eject quickly enough after being struck.

At any rate, by late June 1837, these problems, whatever their nature, had been solved and one of the steam-powered presses had struck more than 400,000 cents in the preceding two weeks without interruption except, one presumes, for the changing of the dies. This works out to something better than 50 coins per minute, certainly a respectable showing for the period of early steam-powered coinage.

The odd delay may tell us that there were two deliveries of the coin prior to Feb. 22 but that they were all melted. It is possible, for example, that half dollar coinage resumed in January 1837 with the old screw press and, for whatever reason, the entire mintages of the two missing account numbers were simply melted.

Once the Mint resumed striking silver in the latter part of February, gold was not far behind. However, for the time being, half dollars were not struck in large numbers because the steam press then in use was meant for smaller coins – no larger than a copper cent – and work went slower as a result. The larger press was ready in due course, but not until a few weeks later.

In the meantime, one of the most interesting silver coins of 1837 was struck and about which there is still controversy. In December 1836 one thousand Gobrecht silver dollars had been struck as circulating coins but in late March 1837, there was a further coinage of 600 Gobrecht dollars.

Recent scholarship has shown that these 600 dollars of March 1837 were actually a test run on the new steam coining press. The 1000 pieces of December 1836 had been struck on the medal press without any problems but it was important to coin dollars on a steam press for efficiency. Because it was merely a test coinage run, the 1836 dies were used with the dies in medal turn. (In a medal arrangement the coin is turned side-by-side to show the reverse properly.)

The “medal” alignment was done for two reasons. The first, and perhaps most important, was that these March 1837 dollars were struck under the new law of January 1837 which mandated a silver fineness of 900/1000 rather than the .8924 used prior to that year. The second reason is more complex but it is known that Patterson did not like using outdated dies and the alignment change enabled an easy distinction between the December 1836 and March 1837 issues.

The 1837 coins are controversial because the dollars dated 1836 were restruck in the late 1850s but until the 1970s there was no way of distinguishing originals from restrikes. However, it is now known that originals of March 1837 in “medal” alignment are originals if and only if the eagle is flying “onward and upwards” – the so-called Die Alignment II – when the coin is properly rotated. All other pieces are restrikes from the 1850s.

Original Gobrecht dollars of March 1837 are extremely rare and it is a fortunate collector indeed that possesses one of these interesting coins. Because they are an absolute necessity for a complete variety set of United States silver dollars, there has been pressure from some collectors and researchers in recent years to classify restrikes as originals, a movement which has served only to confuse the true facts of the matter.

The dollars of 1837 are very rare because the regular mintage of 600 pieces was not released to the public but rather melted in November 1839. The only known original 1837 dollars are those proof pieces struck for collectors in honor of the new .900 fineness stipulated by the January 1837 mint law.

Gobrecht dollars were not the only design changes seen on coins of 1836–1837. Engraver Christian Gobrecht was also making small modifications to the obverse cent design in order to make it more pleasing to the eye. In 1835 there had been a major improvement and this was followed by other changes until Gobrecht and Patterson were generally satisfied with the new head of Liberty that came in 1839.

Director Patterson was so pleased with the artistic success of his new dollar that he planned to use the Seated Liberty motif on other silver coins as well. His first choices fell on the dime and half dime and the engraver was ordered to begin work on new dies for these denominations. Unlike the pre–1837 coins of these denominations, however, the law of 1837 specified that the value was to appear in a wreath rather than an eagle as had been seen since 1794. This made the reverse dies easier to prepare but also meant that coins would be more easily struck, there being no high points from the eagle to impede the obverse design being fully brought up.

By June 1837 all was in readiness, or nearly so, and Director Patterson asked for formal permission to begin striking Seated Liberty dimes and half dimes. Treasury Secretary Levi Woodbury showed the prototype coins to President Martin Van Buren and both agreed that the change was a major artistic improvement to our coinage; permission was quickly granted.

There were the usual delays at the Mint while technical problems were sorted out, but in late June the first Seated Liberty dimes were minted, followed shortly thereafter by the new half dimes. As was usual during this era there was little overall public reaction to the new designs.

These new small silver coins of 1837 are also special in that there are no stars on the obverse. This was deliberate; in that the Gobrecht dollars dated 1836 also did not carry the usual stars on the obverse but did have them on the reverse.

For 1838 Patterson changed his mind about the obverse design of the dime and half dime and ordered that 13 stars surround the seated figure. Oddly enough, however, the dies sent to New Orleans in 1838 for these denominations had obverses without stars even though stars were already being used in 1838 at Philadelphia. (The New Orleans Mint opened in 1838.)

As with the 1837 silver dollar coinage (with dies of 1836) the no-stars dimes and half dimes of 1837 (or 1838 at New Orleans) are necessary for a complete type set of silver coins. Unlike the Gobrecht dollars of 1837, however, the dimes and half dimes without stars are easily obtained, the only consideration being the amount a collector is willing to pay for a higher-quality specimen.

Quarter dollars of 1837, as opposed to the smaller silver coins, are very much like their counterparts of 1836 and there is nothing to distinguish them from one another except for the change in weight and fineness. In a similar vein, the half dollars of 1837 are virtually identical to the scarce reeded-edge pieces of 1836 except for weight and fineness.

On the 1836–1837 reeded-edge halves the denomination is changed to “50 CENTS” in place of the old “50 C.” but in 1838 this was changed once more, to “HALF DOL.” The 1837 half dollar, as with the other silver coins of this date – except for the quarter dollar, thus becomes another coin necessary for a complete variety set.

Unlike the dime and half dime, the half dollar dies sent to New Orleans for 1838 were of the new design rather than that used in 1837. The 1838–O half dollars were struck in a few pieces, less than 20, in early 1839. Because so many half dollars were struck at Philadelphia in 1837, however, that coin is easily obtained.

Gold coins of 1837 are mildly scarce for the half eagle and more so for the quarter eagle. The designs had been revised in 1834, when the weight had been lowered, but Patterson had never been all that pleased with the changes and Gobrecht executed a revised head of Liberty in 1839 for the half eagle (1840 for the quarter eagle), which was to remain in use for nearly 70 years.

The law of January 1837 also changed the fineness and weight of the gold coins by a small degree and, as with the silver coinage, coins of this year (or 1838 for the half eagle, 1838–1839 for the quarter eagle) are needed for a complete type set. These can be obtained without too much trouble, however, for both denominations.

Much of the gold struck in 1837 came from the French Indemnity. President Andrew Jackson had pressed the French government very hard over some debts owed from the Napoleonic era. In due course the payments, mostly in gold, began to arrive and were coined at the Mint.

For those collectors wishing a real challenge, putting together a complete set of the 1837 coins is not an easy task, especially for the Gobrecht dollar struck with 1836 dies in March 1837. Most of the other coins are obtainable with relative ease but in the highest grades there will be problems.♦