Study Seeks Source of Silver For Roman Coins

The United States proudly trumpets that our gold and silver American Eagle coins are made from precious metals exclusively mined domestically. Have you ever wondered just how much metal that…

The United States proudly trumpets that our gold and silver American Eagle coins are made from precious metals exclusively mined domestically. Have you ever wondered just how much metal that goes into minting coins may have originated somewhere other than in the country in whose name those coins have been struck?

Regarding the United States, we know the nickel used in many of our minor denomination coins originated from domestic mines controlled by a monopolist who lobbied Congress to use his metal. The Morgan silver dollar was produced using metal forced on the government through legislation. This appears to be the great American way!

What about the copper used in our half cents, cents, and 2-cent coins? Scrap metal retrieved from barrel hoops was used on occasion. Blanks were purchased from outside the United States at one time. At another time foreign tokens were used as the host planchet for U.S. copper coins.

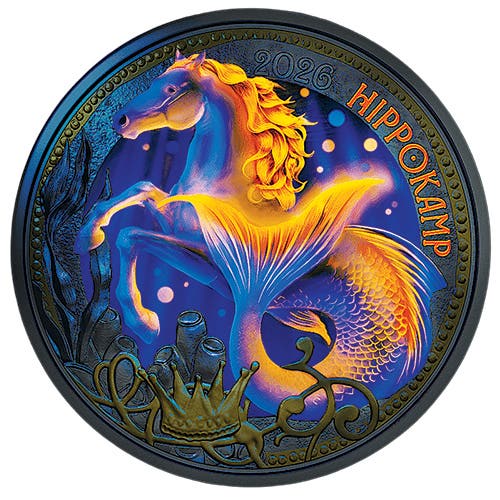

The metal used in coin production has been coming from foreign as well as domestic sources ever since the coin was first invented. A recently published study of the source of silver for ancient Roman coins authored by Jean Milot appears in the journal Geology.

According to Milot, “The control of silver sources was a major geopolitical issue, and the identification of Roman silver sources may help archaeologists to reconstruct ancient fluxes of precious metals and to answer important historical questions.”

Milot continued, “This work needs to be extended to the silver-rich region in which coinage was invented in the 6th century B.C.E, Greece and Asia Minor (modern Turkey). The method we describe here will allow us to recognize the lost ore fields which supplied silver to the Eastern Mediterranean empires from the Bronze Age to the collapse of Hellenistic kingdoms.”

Milot identifies the Iberian Peninsula, currently encompassing Spain and Portugal, as the source of world class silver deposits. These deposits contain galena, a source of silver as well as of lead. To extract silver from such ore the galena is smelted and purified, leaving the silver behind. According to Milot, the silver from this source was able to have a purity exceeding 95 percent.

Silver and lead originating from galena samples was analyzed and compared to the chemical signature of silver composition Roman coins. Milot said two different types of galena deposits were identified based on the silver in the coins. The silver-rich galena would have been a likely source for Roman coinage, while silver-poor galena would have been exploited for lead only, according to the study. The silver-poor galena would have been of lower economic importance. Milot observed that Roman coins notably have a very narrow elemental composition range.

The results based on chemical analyses are also consistent with archaeological evidence for ancient mining exploitation in the region.

By 53 B.C. Rome had expanded its influence throughout much of the Mediterranean region, including Iberia, modern Spain, and Portugal. As the republic and later the empire expanded the need for metal for coinage and other purposes expanded as well. Central Italy is not rich in metal ores, necessitating trade to acquire Rome’s needs. Due to Rome’s acquisitions due to victory in the Punic Wars minerals could be mined in Iberia and Transalpine Gaul. Roman mining operations would eventually expand into northwest Africa, Egypt, Dacia, Noricum, Arabia, Germania, and Britain.

In his 2002 book Machines, Power and the Ancient World Andrew Wilson wrote that hydraulic mining using hushing and ground-sluicing was operated on a large scale by the Romans. Roman mining was able to extract metals on an industrial scale “only rarely matched until the Industrial Revolution.”

By the second century a system of convicts acting as indentured servants replaced slave labor in the mines due to production costs. The Emperor Hadrian gave control of the mines to private employers, but this law was rescinded in A.D. 369. Roman poet Decimius Magnus Ausonius speaks of using a water mill for sawing stone in his fourth century A.D. poem Mosella.

The most important contemporary source of Roman mining and metal development can be found in Naturalis Historia (books XXXIII-XXXVII) by Pliny the Elder.