Queen unites Scandinavia – sort of

By Bob Reis We were talking about Albert of Mecklenburg, a German interloper who was recruited by a faction in Sweden to be a puppet king, ruled perhaps somewhat injudiciously,…

By Bob Reis

We were talking about Albert of Mecklenburg, a German interloper who was recruited by a faction in Sweden to be a puppet king, ruled perhaps somewhat injudiciously, his incompetence setting in motion other political activities by the other interested power position, specifically the Danish crown, the Norwegian crown, and the Swedish nobles, or rather, some of them.

I find it helpful to think of those movers and shakers back then as big time gang leaders, constrained more by necessity than by legal or ethical considerations. An extreme oversimplification, I know, but still: they were individual people with the asserted right to do whatever they wanted. They were all the time coveting and resenting and scheming and fighting. Our leadership these days somewhat pretends to consult we who don’t lead and to do what they do for our benefit. Back then no, it was personal glory. The peasants are going to live and die for that.

There you are tilling your field by hand. Here comes the king’s guard, “Come with us,” you don’t say, “My wife’s having a baby as we speak,” or “I broke my thumb yesterday.” You just go. They march you alon and give you a pole or something. There you are, somewhere, trying to kill someone just like you who’s trying to kill you back.

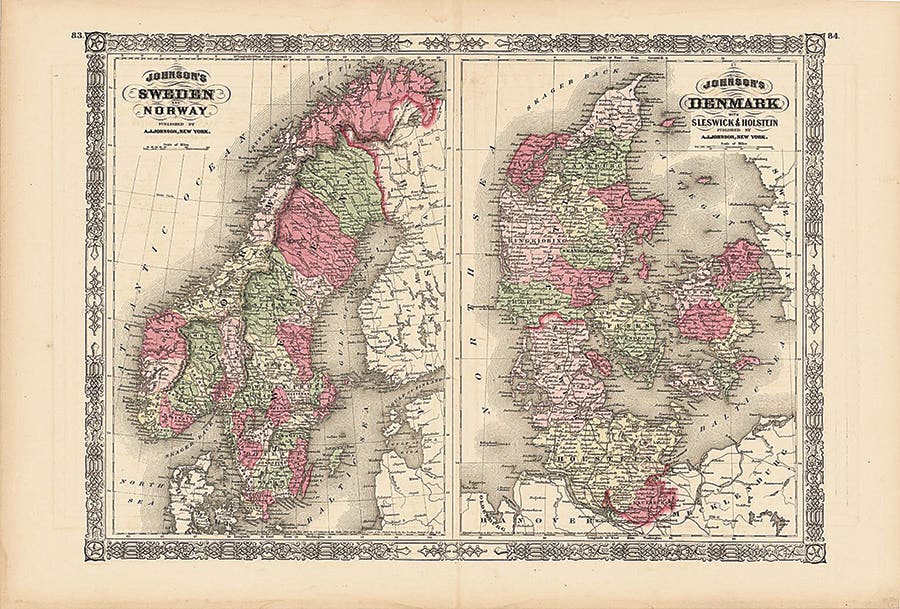

We had been discussing late 14th century Swedish history. Up to now the situation, summarized to a fare-thee-well, was this: three kingdoms, all the monarchs related by blood or marriage, Sweden the backward child of the bunch, Denmark closest thing to the wise elder. Finland was populated by wild tribes according to the general opinion back then. There was a commercial confederation of German merchant towns, the Hanseatic League, that was acting something like later colonial enterprises did: traveling abroad, making trade deals with locals, establishing settlements, eventually accruing mercenaries to enforce their contracts. There got to be a lot of Hansas in Stockholm, and on Gotland island. Their opinions got to be important.

Let me write about Margaret of Denmark, the person who set the stage for the drama of 15th century Scandinavia. She was the last child of the Danish king, betrothed at age 6 to one Haakon, 18-year- old son of the king of both Sweden and Norway, Magnus IV (of Norway) and VII (of Sweden). You see what they’re trying to do there, right?

Various military and diplomatic adventures proceeded while Margaret was growing up. There was civil war in Sweden involving the king and another of his sons. Denmark got involved in favor of the father, but the kid died, and it wasn’t as if Valdemar of Denmark and Magnus of Sweden were friends or anything, so the marriage contract between daughter of Denmark and son of Norway and Sweden was put in a cabinet, the Danish troops sent to help the Swedish king repurposed to poach Swedish territory, such as Scania, separated from Denmark by about 20 miles of water, and Gotland island, the commercial key to the Baltic sea.

Swedish Magnus, being on the outs with Denmark, must naturally now be allied with the Hansa, and a German duke’s boy was found for Margaret, but, they say, the boat she was taking to Germany was driven by bad weather to an island where an archbishop heard about it and declared the German contract illegal, far as he was concerned the original contract with Haakon, son of Magnus, was still in force. Hmm. Anyway, Margaret and Haakon were married the next year, 1363. She was 10 years old. The next year her husband’s father was deposed and driven out of Sweden by Albert of Mecklenburg.

Her father died in 1375, Margaret was 22. She immediately moved to get her baby Olaf elected king of Denmark, herself as regent. The other major contender was a Mecklenburg. Olaf was automatically heir to Norway, and she managed to get him proclaimed rightful heir to Sweden, in formal possession of that interloper, Albert of Mecklenburg.

Margaret’s husband, Haakon, king of Norway, died in 1380, succeeded by her son, Olaf, then 10 years old, Margaret regent. She was well liked by the ruled. Every chance that came up people wanted her to run things for them. But Olaf died in 1387 before his majority. The Norwegians asked her to be regent.

Then she was invited by a Swedish faction to help get rid of Albert of Mecklenburg, which she did, and gave her what she wanted, which was to select the next king of Sweden. Thus did Margaret sweep the table in Scandinavia.

She ruled as regent until 1396/7, in which period she arranged for a nephew, Eric of Pomerania, to be crowned king of all three Scandinavian kingdoms. She engineered a treaty, known to history as the Kalmar Union from the city in which it was announced, that pointed toward a permanent alliance between Denmark, Norway and Sweden. It didn’t last, as we know, but it endured for about a century, and it set a standard for, let us say, perhaps, etiquette in the conduct of political affairs in Scandinavia, a level of comity to be striven for even if impossible to attain.

No coins for this giant of Scandinavian history. Margaret had to find males, or in her case a single male, of proper lineage to sit on the thrones.

Eric of Pomerania was born with the name Boguslaw, which is of course Slavic, his Nordic name was in the way of a propaganda exercise to improve his profile. After some years of negotiation he was married to a daughter of the king of England.

What was Eric like? They say he was handsome and outgoing. They also say he was not a great negotiator, and his war making typically did not accomplish his purposes. Disputes in Pomerania and other lands south of Denmark, that is, Germany, did not go well.

His most lasting project was the institution of an enforceable toll system on the only entrances to the Baltic Sea, the revenues going to the crown, that continued until the 19th century, reducing the power of Danish nobles and crimping the potential of Sweden and Norway, as well as burdening the German Hansa League, leading to war with the Hansa and rebellion, first in Sweden, then in Norway. Long story short, he was deposed by the noble councils in all three of his countries. He “retired” to Gotland island, where he made a living as a toll collector (or pirate., depending on your point of view) for 10 years, then went back to Pomerania to sulk, where he died in 1459.

Eric did issue coins, apparently in all of his domains, that is: Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Pomerania. There may be other issues from lands he held ephemerally during his wars. In my web search I found a Hungarian coin that referenced him in its description, though I did not dig deeper on it. In Sweden there were ortugs, the local version of the penny, struck in Stockholm. I saw two types: one an English style facing portrait, the other a three crown shield displaying the union of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. Reverse type was an “E” on a long cross. Prices I saw are in the $100-$300 range. They seem to be scarce.

Eric’s replacement, in all three countries, was a nephew, Christopher, of the Neumarkt counts palatine, which is to say, nothing special in the royal candidate field, except he was a relative, known to history as Christopher of Bavaria. He was meant to be a puppet, but he managed to do some things in his few years as monarch of all of Scandinavia, such as establish Copenhagen as capital of Denmark, and defeating a peasant rebellion there, after which he established serfdom. In Sweden there was famine. He died, I read, “suddenly,” in 1348, his widow marrying his successor in Denmark.

There is, for me, a kind of absentminded, get to it later feeling to 14th century Scandinavian coinage. At that time they were making $5 weight gold coins in France and England and the Low Countries, and big silver groats, and lots of pennies. In Germany there was coinage all over the place. In all three Scandinavian countries it was more like, here’s a coin, another one there, a lot of nothing, then another isolated coin issue of low output and limited circulation. It was like they’d put out a coin to prove they could, meanwhile the commerce was being done by Hanseatic Germans with Hanseatic German coins.

I went looking for coins of Christopher of Bavaria, but I didn’t find any.

This whole 14th century Scandinavian scene has for me a backwater feel to it. Like, oh, Somalia might be to Egypt, or Honduras to the USA. The money and power are here, not really caring about the periphery, “there,” even though peripheral events occasionally affect things in the center, from time to time drastically. Center thinks, can’t do much about “there” anyway, this is generally proved over and over again in history. They gonna do what they gonna do anyway.

I think its fair to say that the monarchs and their governments in 14-15th century Scandinavia, with the outstanding exception of Danish queen Margaret, were undistinguished at best, variously incompetent mostly.

Christopher of Bavaria was succeeded by one Karl Knuttsson, who had a connection with the various branches of the Swedish royals so ephemeral that its not, in my opinion, worth describing. You had to have some kind of personal relationship with some former monarch to be allowed to try for a crown. Lars Petersson of the next farm over was not eligible. The only way he could have been would have been for an ancestor to have been knighted by a previous king, then further honored with a hereditary title, then the family would have had to marry into some piece of the royal family. Otherwise forget it.

That’s why people were going around then with fake genealogies from some far away land, maybe they could marry well and off to the races.

Remember how the prince of Monaco became a prince? He signed a letter to the king as “prince,” the royal letter reader let it pass, poof! He’s a prince.

Karl, let’s call him Charles, because in English that is typically how the so-named kings of Sweden are styled, has two numbers by which he is referred: VIII and II. This is because Charles IX of the early 17th century adopted his number based on a fictitious history of Sweden that included a number of monarchs of various names not found in any real records. Bunch of Charleses, Erics, Olafs. So if Charles IX added some numbers to his name because of a fairy tale and MADE IT OFFICIAL, well, that’s the way it is, and other innocent monarchs are going to get their numbers changed too. We don’t know if the Charles who was king of Sweden after Christian of Bavaria thought of himself as Charles II or just as Charles, but to us, today, he is Charles VIII.

We’ll discuss him and his paltry coinage next time.

This article was originally printed in World Coin News. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• The Standard Catalog of World Coins, 1601-1700 is your guide to images, prices and information on coins from so long ago.

• More than 600 issuing locations are represented in the Standard Catalog of World Coins, 1701-1800 .