How much was it worth in 98 B.C.?

By Richard Giedroyc Collectors may ponder what a coin would purchase in its own time. It can be difficult to comprehend that the average American worker earned about a dollar…

By Richard Giedroyc

Collectors may ponder what a coin would purchase in its own time. It can be difficult to comprehend that the average American worker earned about a dollar a day during much of the 19th century. If an individual carried a $5 half eagle gold coin in his pocket he was carrying his wages for a week in one coin! What do you think an ancient coin of Egypt, a Greek city-state, or from Rome might have purchased?

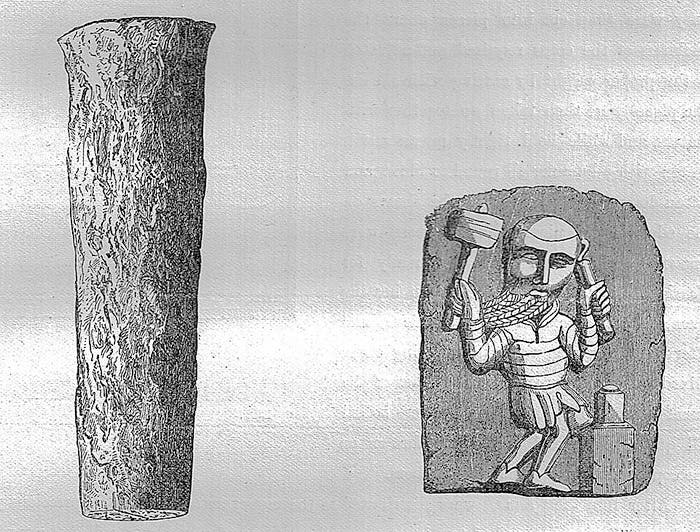

This same question was recently raised regarding an ancient Egyptian tax receipt inscribed on an ostracon or potsherd. The potsherd inscription is for a land transfer tax being levied by the Egyptian government. The potsherd is currently on display at the McGill University Library and Archives in Montreal, Canada.

According to the March 15 issue of The Cairo Post newspaper, “…where it was found and how it ended up [in] Canada remains unknown.”

The March 16 issue of Discovery News reported the inscription is written in Greek. The inscription accounts for a person whose name couldn’t be deciphered and his friends being charged 75 talents for a land transfer, accompanied by an additional 15-talent charge to be paid in coins. This bill was to be delivered to the public bank in Diospolis Magna (also known as Luxor or Thebes). The receipt is dated to our modern calendar equivalent of July 22, 98 BC, during the later Ptolemaic rule of Egypt. The question to coin collectors is—how much in coins are we talking about?

Brice Jones is the doctoral candidate and part-time lecturer at Concordia University in Montreal who translated the potsherd inscription. Jones told Discovery News, “It’s an incredibly large sum of money. These Egyptians were most likely very wealthy.”

Jones was quoted by the ScienceNews.com website as saying the tax receipt “shows a bill that is heavier than any American taxpayer will pay this year—more than 220 pounds (100 kilograms) of coins.”

Fathy Khourshid is a professor of Greco-Roman history at Minya University in Egypt. Khourshid told The Cairo Post Sunday, “The Greek kings imposed the traditional harvest taxes in kind and the occasional sales taxes in money with more regular money taxes.”

The Ptolemaic dynasty was Greek, having descended from one of Alexander III (“The Great”) of Macedon’s generals. Ptolemy X was the sole pharaoh from 101 BC to 88 BC when his brother deposed him.

The 15 talents added to the tax bill is called allage, a charge added because the people paying the land transfer tax failed to pay in silver coins.

Cathy Lorber is a numismatic researcher and auction cataloger. She was quoted by Discovery News as saying, “This was an exchange fee imposed on bronze currency when it was used to pay an obligation that legally should have been paid in silver. This system was maintained even in periods when silver coinage was scarcely available.”

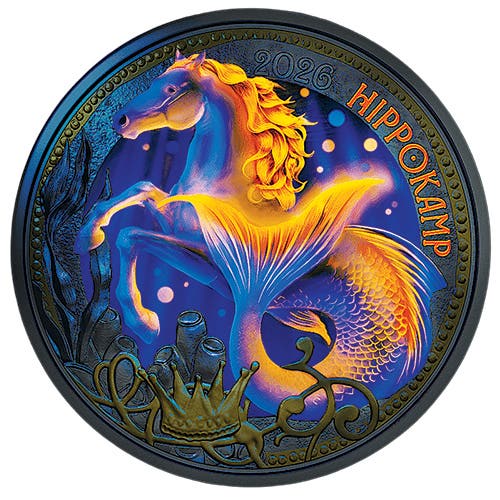

About 98 BC one talent was valued at 6,000 drachma. The 90-talent tax bill would have totaled 540,000 drachma. Ptolemaic coins included several bronze denominations as well as silver drachms, didrachms, tetradrachms, and significantly rarer higher denominations.

There were several larger denominations in gold as well. The largest denomination coin of the time is believed to have been valued at 40 drachms. An unskilled laborer earned about 18,000 drachma annually.

LiveScience.com asked Lorber to calculate the number of coins the 98 BC transaction would have involved. Lorber calculated if the coins averaged eight grams or about 0.3 ounces each in weight it would take 150 coins to equal one talent or 13,500 drachm coins to equal the 90 talents being billed. This enormous number of coins would need to be physically transported to the bank in Diospolis Magna.