The Mystery of Hagerstown National Bank

This month’s article combines some common-sense questions about National Bank Notes and a bit of financial sleuthing to present a very interesting piece of national banking history.

A few years ago, when I was actively collecting national bank notes of my home state of Maryland, I came across three notes from the same bank that piqued my interest. These notes each hailed from the First National Bank of Hagerstown, Md., charter #1431. This was one of the state’s oldest banks from a town that was once Maryland’s second-largest city. Hagerstown is the seat of Washington County, in Western Maryland, about 70 miles due west of Baltimore.

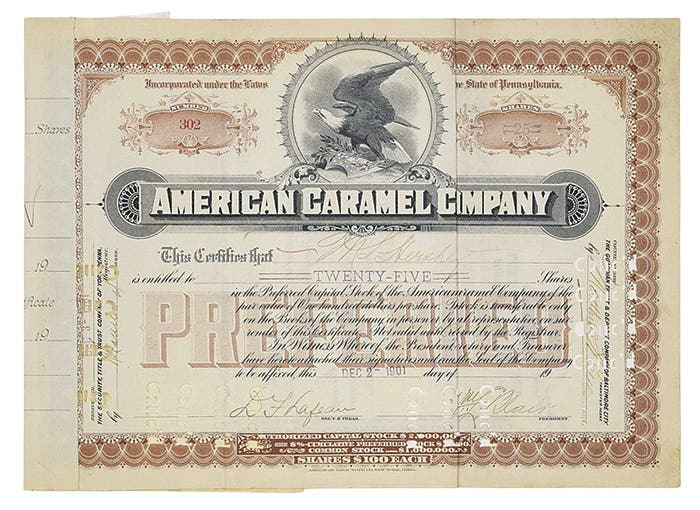

The notes were all in the 1902 Blue Seal series, and what drew me to them was that each of the notes had completely different bank officer signatures. Having examined literally hundreds of national bank notes, it surprised me to see such a complete and total change in officers, not once, but three times in what seemed like a relatively short period of time. Normally, one might see a long-time cashier move up to president, or notes with signatures of assistant cashiers and vice presidents, but these notes bore completely different signatures of cashiers and presidents; none were overlapping. I found this rather odd and held on to this trio of notes even when I sold a large part of my collection.

My interest in the history of national banking led me to read the book The Romance and Tragedy of Banking, written in 1922 by the then Deputy Comptroller of the Currency, Thomas P. Kane. Kane wrote about interesting situations regarding national banking that he had encountered in his position. His style was a bit dull and plastic, but the stories added depth to my knowledge of national banking. It did come as a complete surprise, however, when I neared the end of this 500-page tome to find a subheading entitled “First National Bank of Hagerstown.” In one of those wonderful examples of serendipity, I uncovered the explanation for my trio of Hagerstown bank notes.

The First National Bank of Hagerstown was organized on May 2, 1865, by conversion of the Hagerstown Savings Bank to national bank status. It was a large and successful organization with a life spanning over 60 years and a total issue of $2.5 million. The bank was well and conservatively managed over most of its life. The operative word here is “most,” for, in January 1918, a local business family that had managed to acquire a controlling amount of the bank’s stock ousted the conservative management of the bank as a result of a more or less hostile takeover.

The new management was composed entirely of members of the Wingert family. The previous bank regime, headed by President Frank W. Mish and Cashiers Nervin J. Brandt and J. William Ernst, were removed and replaced by brothers Henry F. Wingert and Miller Wingert, who became president and cashier, respectively. Henry F. Wingert was well-known in the community: lawyer, owner of a local furniture company, and county politician. His brother Miller was also a lawyer and a prominent local farm owner.

As Deputy Comptroller Kane described it, “It would appear that for the next three years, the Wingerts’ bank was a most persistent violator of the law, not only deliberately ignored the instructions of the national bank examiners at each examination but openly and continuously defied the admonitions and repeated warnings of the Comptroller of the Currency.”

In plain English, the Wingerts took control of a very reputable banking institution and then went about using the bank’s assets as their personal funds. Loans were made to family, friends, and associates without proper collateral and for the Wingerts’ own investment schemes. The Wingerts seemed to have hit the jackpot! Merely by acquiring a controlling amount of the bank’s stock, they literally had the bank’s millions at their beck and call and seemed to decide on a willy-nilly basis which of the national banking laws actually applied to them. For the Comptroller of the Currency, this was a serious mess.

Accordingly, on Sep. 28, 1921, a lawsuit was filed in the U.S. District Court at Baltimore, in the name of the Comptroller, to annul the charter of the First National Bank of Hagerstown for violations of the national banking laws. The charter of other national banks had been revoked by order of the courts from time to time for various reasons, but this was the first and only time in the history of the national banking system that a suit was brought to revoke the charter of an active national bank for violations of the banking laws in the conduct of its business.

Interestingly, though the Wingert management had violated the laws on a wholesale basis, the bank was not insolvent. The court, fearful that the mere filing of the suit would precipitate a run on the bank, appointed a national bank examiner as temporary receiver and ordered him to take immediate control of the bank and its assets. This was the first time that a court had ever appointed a receiver (that job was normally left to the Comptroller when a bank became insolvent), and thus, the court’s authority to do so was in serious question.

Before the suit actually got underway, however, and before the opportunity to question the court’s authority became available, the Wingerts threw in the towel. Henry Wingert approached the U.S. Attorney in Baltimore and proposed to remove his family from the operation of the bank altogether, sell all their shares, and have a completely new board of directors and a slate of officers appointed from reputable banks who had no relationship to the Wingerts. The Comptroller agreed to this, and the suit was subsequently withdrawn. I have included a photo of Henry Wingert above his signature, which you can compare to the signature on the bank note.

A new board of directors, consisting of prominent statewide bankers and members of the community, was appointed. The former Attorney General of the State of Maryland, Alexander Armstrong, became president of the bank. On Oct. 8, 1921, the bank reopened under entirely new management.

The trio of notes that I had so wisely chosen to save accompanies this article and represents the volatile history of the bank. The first note, a Series of 1902 $20 Date Back, bears the signatures of Nervin J. Brandt, cashier, and F.W. Mish, president. These were the honest officers of the bank prior to the Wingert takeover.

The next note, a 1902 $10 Plain Back, was issued between 1918 and 1921 and bears the signatures of the Wingert brothers as cashier and president.

The third note, also a $10 Plain Back, was issued after October 1921 and bears the signatures of Benjamin W. Saxten, cashier, and Alexander Armstrong, a gubernatorial candidate and former Attorney General of Maryland, as the new president. Armstrong ran the bank for ten years until it succumbed to the Great Depression and was closed by the receiver in 1931.

See also a small note bearing Armstrong’s signature and that of cashier Edwin J. Smead, who served from 1924 to 1931.

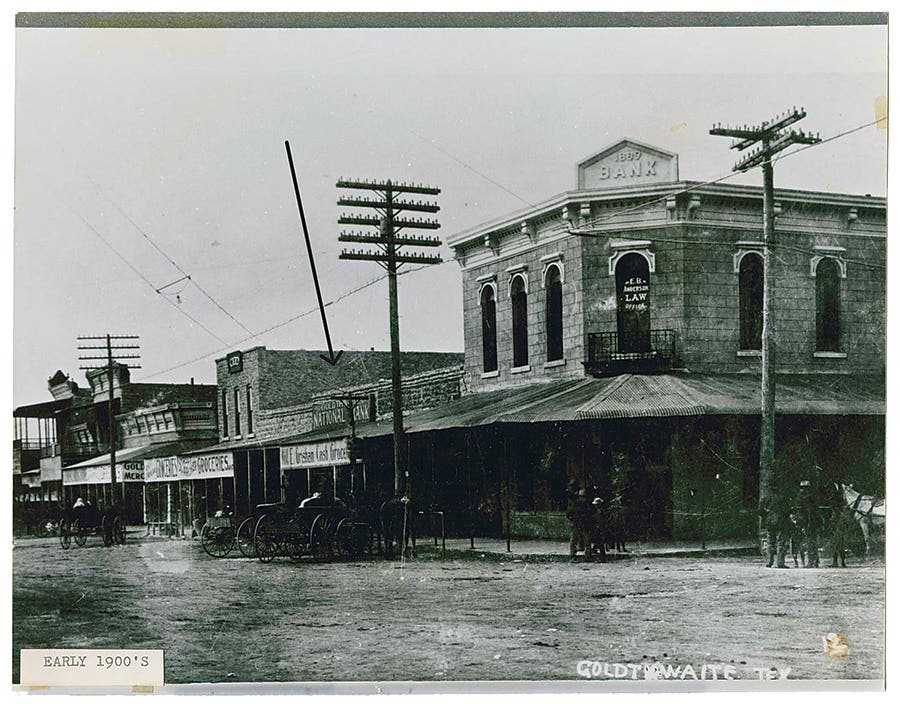

I have included a vintage postcard view that shows the First National Bank of Hagerstown’s 6-story building as it appeared in 1918 and today. The building has been converted to office/residential space and as you can see the entrance has been architecturally altered.

Readers may address questions or comments about this article or national bank notes in general to Mark Hotz directly by email at markbhotz@gmail.com.

You may also like: