The History-Rich Ghost Town of Cairo, Ill.

Cairo, Illinois, was once a bustling commercial center with a robust population. Everything has gone downhill since.

For this month, in honor of the American Numismatic Association’s 133rd Anniversary of the World’s Fair of Money Convention in Rosemont, Ill., I am continuing last month’s Illinois sojourn with a visit to one of the most intriguing ghostly cities in America: Cairo, Ill., along the Mississippi River.

Cairo (pronounced Care-oh) is the southernmost city in Illinois and the county seat of Alexander County. A river city, Cairo has the lowest elevation of any location in Illinois and is the only Illinois city surrounded by levees. It is in the river-crossed area of Southern Illinois known as “Little Egypt,” for which the city is named after Egypt’s capital on the Nile.

The city is located at the confluence of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, two of the largest rivers in North America, and is near the Cache River complex, a wetland of international importance. Settlement began in earnest in the 1830s, and busy riverboat traffic expanded through the 1850s. Fort Defiance, a Civil War base, was located there in 1862 by Union General Ulysses S. Grant to control strategic access to the rivers and launch and supply his successful campaigns south. Developed as a river port, Cairo was later bypassed by transportation changes away from the large expanse of low-lying land, wetland, and water that surrounds Cairo, and due to industrial restructuring, the population peaked at 15,203 in 1920, while the 2020 census was 1,733.

Before it became Cairo, Ill., the area was a fort and tannery for some of the first French traders who arrived in 1702. However, their operation was cut short after Cherokee warriors slaughtered most of them. A century later, the area at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers played a role in the Lewis and Clark expedition, as the explorers camped there while learning how to determine latitude and longitude. According to James M. Lansden’s A History of the City of Cairo, Illinois, John G. Comegys of Baltimore bought 1,800 acres in southern Illinois in 1817 and named the land “Cairo” in honor of the historic city of the same name on the Nile Delta in Egypt. Comegys hoped to turn Cairo into one of America’s great cities, but he died before his plans could be realized. The name, however, stuck.

It wouldn’t be until 1837, when Darius B. Holbrook entered the town, that Cairo really took off. Holbrook, more than anyone else, was responsible for the city’s establishment and early growth. As president of the Cairo City and Canal Company, Holbrook set a few hundred men to work constructing a small settlement that included a shipyard, a farm, a hotel, and several residences. However, Cairo’s susceptibility to flooding was a major obstacle in establishing a permanent settlement. Holbrook’s plan initially faltered as the new town’s population fell by more than 80 percent.

Indeed, not everyone shared Holbrook’s optimism. When Charles Dickens visited Cairo in 1842, he described it as a “detestable morass” and a “breeding place of fever, ague, and death.” He purportedly based the hellish city of Eden in his novel Martin Chuzzlewit on Cairo.

Holbrook, however, remained confident. Despite earlier disappointments, he next sought to add Cairo as a station stop along the Illinois Central Railroad. By 1856, Cairo was connected by rail to Galena in northwest Illinois. This set Cairo on the path to becoming a boom town within just three years. Cotton, wool, molasses, and sugar were being shipped through the port in 1859, and the following year, Cairo became the seat of Alexander County. By the outbreak of the Civil War, Cairo’s population was 2,200 — but that number was about to explode.

The city’s location along both a railroad line and a port was strategically important, and the Union capitalized on this. In 1861, General Ulysses S. Grant established Fort Defiance at the tip of Cairo’s peninsula, which operated as an integral naval base and supply depot for his Western Army. With a growing population and commerce, Cairo was poised to become a major city. Some even suggested that it should become the new capital of the United States. However, the troops did not like the humid climate, which was made worse by the muddy, low-lying land that was so susceptible to flooding.

Future Secretary of the Treasury George S. Boutwell wrote “Our life at Cairo was disagreeable to an extent that cannot be realized easily.” As a result, when the war ended, the soldiers packed up and went home. Despite the post-war population exodus, Cairo’s location and natural resources continued to attract breweries, mills, plants, and manufacturing businesses. Cairo also became an important shipping and steamboat hub. By 1890, the town was connected to the rest of the country by water and several railroads, and it acted as an important way station between larger cities.

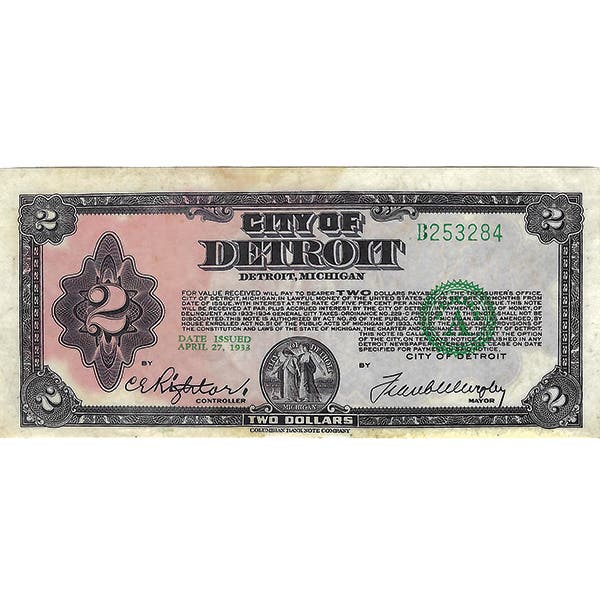

With progress came banking. Cairo was eventually home to five national banks: the First National Bank of Cairo, charter #33, opened in 1863 and liquidated in 1874. No notes are known from this issuer; the City National Bank of Cairo, charter #785, opened in 1866 and liquidated in 1907. Five notes are reported from this bank: the Alexander County National Bank (the focus of this article), charter #3735, opened in 1887 and liquidated in 1928; the Cairo National Bank, opened in 1903 and liquidated in 1930; and the Security National Bank of Cairo, charter #13804, a small only issuer that opened in late 1933.

In general, notes from Cairo are scarce and not frequently offered. Of the three latter banks, a dozen notes are known from the Alexander County National Bank, 20 from the Cairo National Bank and 15 from the Security National Bank.

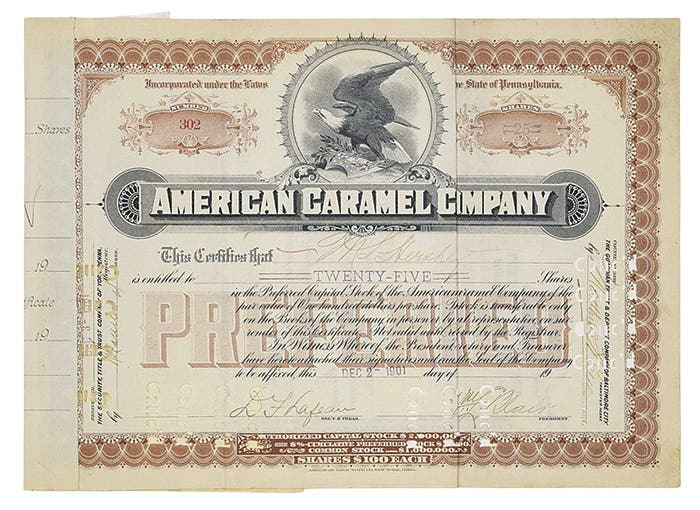

This article will concentrate on the Alexander County National Bank and the City of Cairo in general. The Alexander County National Bank was chartered in 1887 with Fredolin Bross as president and Henry Wells as cashier. The bank was not a large one; its total circulation was $517,000 over the 41 years it operated prior to liquidation at the end of April 1928. For most of its life, it had an annual circulation of $25,000; in later years, that rose to 30 and later $40,000. Two $5 Brown Back notes are known; one is a serial #1 in an institutional collection. Most of the known notes are Series 1902 Dated and Plain Back issues.

As you all know, I am fascinated with ghost towns, and Cairo is considered to be a ghost city today despite the fact that it still maintains a population. The more I learned about Cairo, the more I wanted a note for my collection. I was very pleased to obtain a Series of 1902 $10 Date Back in PMG AU58 EPQ from the Alexander County National Bank for my holdings. It is a lovely, fresh note (not sure why it is graded AU) with superb pen signatures of E.A. Buder, president, and J.H. Galligan, cashier.

Cairo today is a shadow of its former self. A walk or drive through Cairo will find it eerily empty. The historic downtown area, once bustling, is now filled with crumbling brick and plywood-covered windows. Cairo has been decaying for decades, and currently, the business district is virtually totally boarded up, tumbling down, or razed. The deterioration has slowly made its way “uptown” (northwest) into residential neighborhoods as well.

The town has mostly been abandoned because of its economic desperation, though its history of racial tension and periodic flooding certainly didn’t help. The Civil War Reconstruction period brought a migration of formerly enslaved people to Cairo. Racial tensions were always high in the community, but as the shipping and ferrying industries declined, jobs grew scarcer, and the racial unrest intensified. In the mid-1960s, the alleged police murder of a young black soldier on leave in Cairo prompted protests and riots, and the National Guard was briefly activated. In response to perceived threats from the black community, the white community formed a civilian militia called the “White Hats.” Predictably, the group was more focused on quelling black protesters than on improving the community as a whole.

The racial unrest and economic shortsightedness continued, and everything in Cairo organically declined over the decades to come. Some of Cairo’s black citizens left for more progressive pastures. Many business owners—and a few rather large industries—were economically forced to board up shop. The town’s population, which had been over 15,000 at its peak in the 1920s, had dipped to 6,000 by the ’80s. As of 2020, it was down to roughly 1,500, 75 percent of which is black.

The local government has attempted to revive the city through now-racially integrated historic preservation initiatives, but most of these have failed. The only cultural institutions that have really survived are the few state-owned Victorian manors and the Cairo Public Library. Much of the rest of the town has been abandoned.

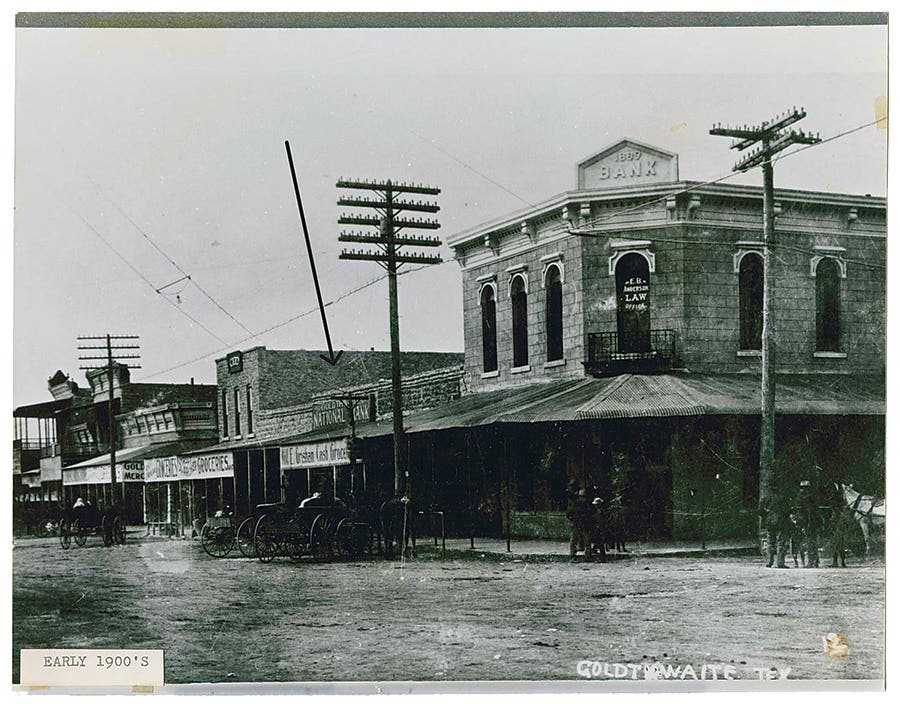

The story of the Alexander County National Bank mirrors that of Cairo itself. Housed in a three-story white-faced brick building, the bank was once one of the major structures on Cairo’s main drag, Commercial Avenue. Most of the once prolific structures that lined that street have been demolished; the bank building was standing until a few years ago, apparently, but had disappeared when I searched for it on Google Earth. I have included a vintage photo of the building as it once appeared and another vintage photo showing it on the crowded Commercial Avenue circa 1920.

Most of the buildings that once comprised Cairo's main business district are gone, leaving a ghostly abandoned aura. However, uptown Cairo still has impressive, preserved mansions and operating businesses, including a Dollar General Store, other churches, and government operations, interspersed with ruined and abandoned homes and other structures. The juxtaposition of the ruins and what clings to life is amazing.

I have included several photographs showing Cairo's deterioration. In an article such as this, it is impossible for me to cover the gamut of Cairo’s impressive history. I would encourage my readers to go onto YouTube and just search “Cairo Illinois” for videos. You will be rewarded with many that explore all of Cairo today and show in real time why the city has earned its ghost town moniker.

Readers may email Mark Hotz directly with questions or comments about this article or national bank notes in general at markbhotz@gmail.com.

You may also like: