Spelling varieties are plentiful

By Peter Huntoon and Robert Liddell Nobody can ever leave anything alone, particularly spellers. That is the point of this column. People often feel compelled to update the spelling of…

By Peter Huntoon and Robert Liddell

Nobody can ever leave anything alone, particularly spellers. That is the point of this column. People often feel compelled to update the spelling of their towns, so this has led to some great variety collecting opportunities for National Bank Note buffs.

What follows is a small sampling of the many unusual occurrences that can be found on National Bank Notes.

Tuskaloosa/Tuscaloosa

Let’s start with a simple example: Tuscaloosa, Ala. Maybe you knew that originally it was spelled Tuskaloosa. We didn’t, and they both sound the same to us. The change came before the Merchants National Bank was organized in 1887, yielding the spectacular large-size threesome set illustrated above.

Muscogee/Muskogee

The same thing happened to Muscogee but in reverse. Getting spellers to go in the same direction is akin to herding cats. Now the place is spelled Muskogee. The change there came just after Oklahoma was admitted into the union in 1907.

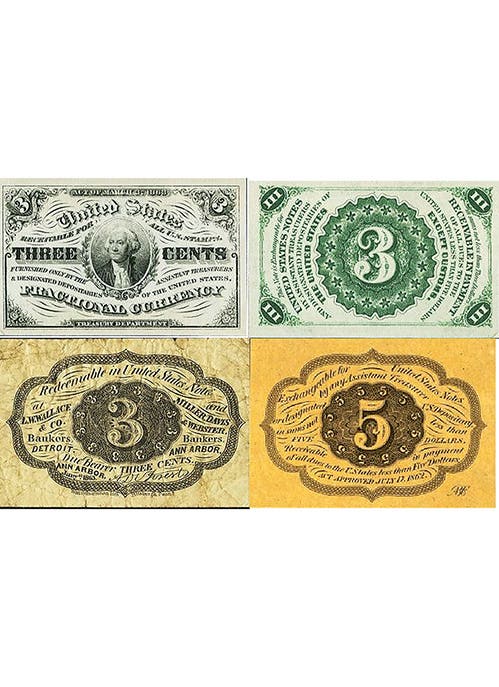

This caused some interagency heat. The comptroller ordered the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to alter all the Oklahoma and Indian Territory plates to Oklahoma state. Muscogee was in the Indian Territory, so the 5-5-5-5 and 10-10-10-20 Series of 1882 plates for The First National Bank were duly altered in December 1907, and the first printings from them were respectively received at the comptroller’s office on Feb. 1 and 3, 1908.

The change in spelling to Muskogee was approved through a formal title change on Feb. 14, 1908. But by then the first state notes had been printed, so the town on them was misspelled.

Those printings had to be canceled, the plates modified once again, and new printings made. Shown above are proofs from the same $5 plate in its three manifestations. Notes are possible only from the first and third varieties.

The change in spelling impacted The Commercial National Bank as well, charter 5236. While they were fixing the plates for The First National Bank, the comptroller also had the BEP update the spelling on the plates for The Commercial National. This was accomplished in April 1908. However, the officers of The Commercial National didn’t file for a formal title change to reflect the new spelling until they extended their charter on July 24, 1919. That was 11 years later.

Why the delay? In 1908, the bank was utilizing three plates, a 5-5-5-5, 10-10-10-20 and 50-100. The bankers wouldn’t file for a title change to fix the spelling because they didn’t want to take the chance of triggering charges of $75 for each for the new four-subject plates, and $50 for the new two-subject plate. The comptroller’s clerks already had authorized the change informally, so it was a fait accompli. The government stuck itself with the tab for doing the good deed.

The cagey bankers figured that by waiting until they extended their bank in 1919, they could apply for the title change then and get the new spelling for free on their new Series of 1902 plates, which they were forced to pay for anyway.

Getting back to The First National situation, the first printings of state 5-5-5-5 and 10-10-10-20 Brown Back sheets from the altered territorial plates with the old spelling already had been shipped during the first three days of February 1908. They carried serials U978484U-U978608U, 1-125, and V6402V-V6501V, 1-100, respectively. Those sheets were canceled and replacements with the new spelling were requested from the bureau.

The bureau personnel altered the plates and reprinted the sheets using the identical Treasury and bank sheet serials as on the original shipment. However, the Treasury serials for the old spelling already were logged into the comptroller’s receipts ledger.

When the new sheets were delivered March 31, the comptroller’s clerks had to deal with the duplicate 5-5-5-5 and 10-10-10-20 Treasury serials.

Well, that caused all kinds of consternation. The upshot was that a curt letter was sent to the bureau asking them never to reuse Treasury serials again because to do so wrecked the books. The same thing had happened 18 years earlier in March and April 1890 with 625 sheets of 5-5-5-5s for The Peirce City National Bank of Missouri (4225). In that case, Peirce had been misspelled Pierce.

The ledger entries for those earlier Peirce City sheets were still causing headaches each time the books were balanced. Now, it was pointed out that between the Peirce City and Muscogee situations there were a total of 750 extra 5-5-5-5 and 100 extra 10-10-10-20 Treasury serials to contend with in the receipts ledgers.

To placate the comptroller’s office, the bureau dropped 750 5-5-5-5 Treasury serials V207839V-V208588V and 100 10-10-10-20 serials V273934V-V274033V from use to balance out the duplicates. A letter dated April 7, 1908, from the director of the bureau to the Comptroller of the Currency confirming this adjustment is pasted into the comptroller’s receipts ledger. The dropped entries also are noted in the receipts ledger on April 10 when those serials would have arrived at the comptroller’s office. The letter is there so future auditors could understand just what had happened.

When it was all over, I bet everyone in the BEP and the comptroller’s office wished that the folks who named their town Muscogee had simply settled for the original name of the Indian tribe after which they named the place. The Muscogees used to be known as Creeks. But then, someone would have wanted to change the spelling to Kreecs.

Pittsburgh/Pittsburg

In 1892, the recently formed Federal Board on Geographic Names published its recommendations. The board had been formed to help standardize and Americanize the spellings of geographic names in use on federal documents. One of their recommendations was to drop the “h” from burghs all over the country. Venerable Pittsburgh, Pa., was specifically targeted.

Five banks adopted the modernized spelling: the Federal, Republic, Industrial, Keystone and American nationals. They were organized between 1901 and 1905, but interspersed among them during the same period were the Cosmopolitan, Mellon, Colonial and Washington nationals, which used the traditional spelling.

The lost “h” did not sit well with some vocal traditionalists because on July 19, 1911, with an effective date of Oct. 11, 1911, Pittsburgh was allowed to retake its “h.” This was accomplished through the good offices of Sen. George T. Oliver, who took an appeal for restoration of the letter on the behalf of the citizens of Pittsburgh to the Board on Geographic Names. It was noted that during the period when the spelling was in transition, all city ordinances and council minutes retained the “h.”

At least national collectors got some nifty varieties out of the bruhaha.

Schellburg/Schellsburg

The folks who named Schellburg, Pa., did their patriotic duty and spelled the place without the “h.” The town was named after a family named Scheller. However, breaking with tradition, they didn’t pluralize it to Schellsburg, which also was rather customary.

This lapse was tolerated for many years. The First National Bank suffered with the peculiar spelling along with everyone else. Finally, the good citizens of Schellburg fixed it by adding the “s.” The title of the bank was altered with the pluralized spelling Schellsburg through a formal title change approved by the comptroller on Jan. 27, 1933.

The result makes for a grand collectable pair in the Series of 1929 shown above.

Vermillion/Vermilion

The original spelling attached to Vermillion, S.D., utilized a double “l” and was the spelling adopted by the officers for The First National Bank of Vermillion when they organized in 1891. Two “l”s were used on all the notes issued from the bank.

The spelling was modified sometime around the turn of the century by dropping an “l,” so that form was used by the officers of The Vermilion National Bank organized in 1904. The one “l” spelling also was used by the officers in The First National Bank and Trust Co. of Vermilion, chartered much later in 1929.

The spelling caused a bit of confusion for the comptroller’s office. It appeared with a double “l,” regardless of bank, in the annual reports through 1906, and a single “l” thereafter.

The spelling problem continued to plague the comptroller’s clerks in 1934, when a change in title for charter 13346 was authorized from The First National Bank and Trust Co. of Vermilion to First National Bank in. The double “l” spelling was used in the list of title changes in the 1934 annual report.

The entry for the new set of logotype plates with the new title, which appears in the billing ledger for 1929 logotype plates, also shows the spelling with a double “l,” even though the spelling for the earlier title appears correctly on the same page. The mystery is what spelling actually appeared on the Series of 1929 Type 2 notes with the First National Bank title. We will have to await the discovery of a note with that title to determine just what happened. Only 199 notes with that title were issued, and currently none are reported.

The fact is that the spelling for Vermillion, S.D., reverted to the double “l” form, which is the standard spelling now employed. The double “l” form is currently used by the post office there.

There was another note issuing Vermilion, this one in Illinois. The First National Bank there, organized in 1913, used one “l.”

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• The Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money is the only annual guide that provides complete coverage of U.S. currency with today’s market prices.

• With nearly 24,000 listings and over 14,000 illustrations, the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, Modern Issues is your go-to guide for modern bank notes.