Original Series charter number over seal varieties

By Peter Huntoon An increasing number of collectors appear to be aware of the charter number over seal variety on Original Series $1 and $2 notes based on inquiries that…

By Peter Huntoon

An increasing number of collectors appear to be aware of the charter number over seal variety on Original Series $1 and $2 notes based on inquiries that I have received. The variety was produced for about two and a half months in 1874 and traces its origin to a hue and cry over the wretched condition of National Bank Notes in circulation and legislation proposed to remedy the problem.

Previously, there was no effective mechanism to cull worn National Bank Notes from circulation, so the stock of national currency in public hands progressively deteriorated. Awareness of germs was gaining traction in public health, so women’s groups in particular seized on the soiled currency as a health hazard and agitated strongly for a remedy. Passage of the Act of June 20, 1874 – which transferred the burden of redeeming worn out National Bank Notes from circulation from the hands of bankers to the U.S. Treasury – was one of the early achievements of the woman’s sanitation movement, a movement that fed into the suffragette movement over the coming decades.

The Act of June 20, 1874, required that charter numbers be printed on National Bank Notes to aid sorting. As a consequence, unissued sheets in the Comptroller’s inventory were returned to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, where the charter numbers were added. New printings carried the charter numbers from the outset.

Treasury officials knew that the legislation was coming, so they began experimenting with means to print the numbers on the faces of Original Series notes before passage of the act. The first appearance came in the form of engraved charter numbers on the face plates for some Original Series $5 plates, printings from which began in December 1873. These constitute our highly prized black charter $5 variety.

Years ago, Doug Walcutt discovered from Comptroller receipts ledgers that the overprinting of charter numbers on new sheets began at least five weeks before passage of the June 20, 1874, act. The Comptroller’s clerks first began recording the charter numbers for new sheets beginning with the 5-5-5-5 combination on May 13, 1874, and next the 1-1-1-2 combination on May 14. However, we discovered from observed notes that at least some of the 1-1-1-2 sheets delivered on May 12 had overprinted charter numbers as well.

The feature that made the earliest overprinted charter numbers on the 1-1-1-2 sheets so interesting is the fact that the charter numbers were printed above the Treasury seal.

As soon as the 1874 amendment was passed, the Comptroller ceased issuing sheets without charter numbers and returned all his unissued stocks on hand without them to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to have the numbers added. However, there wasn’t room above the seals on the returned sheets, so the numbers were printed below the seals.

Unissued Original Series 1-1-1-2 sheets printed from as far back as 1865 were overprinted with charter numbers. Consequently, in the extreme, we can find Original Series $1 and $2 notes that carry unprefixed red Treasury sheet serial numbers printed in 1865 that bear charter numbers overprinted in 1874.

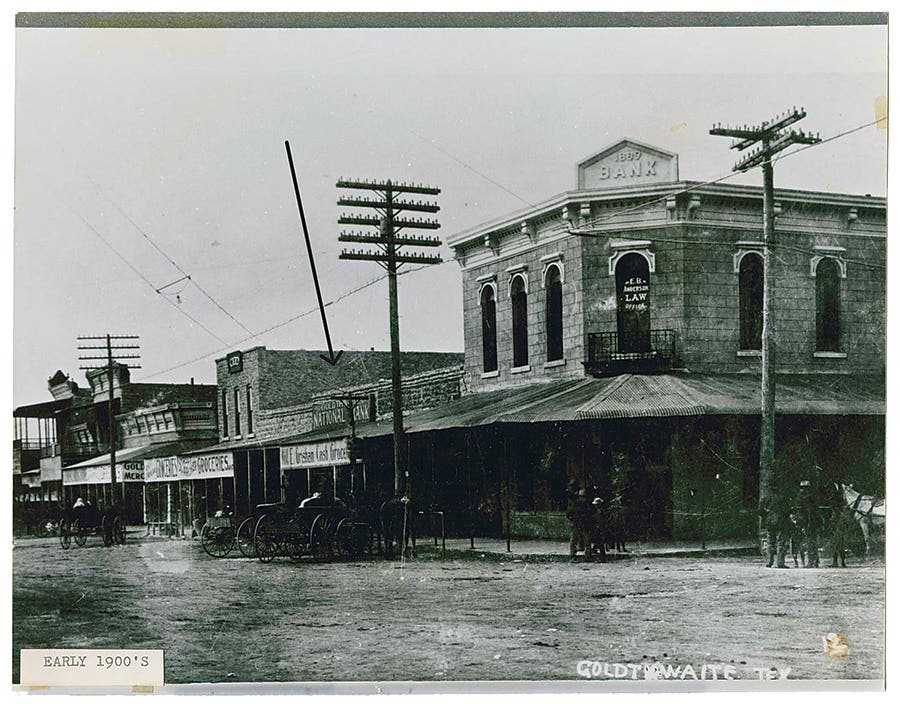

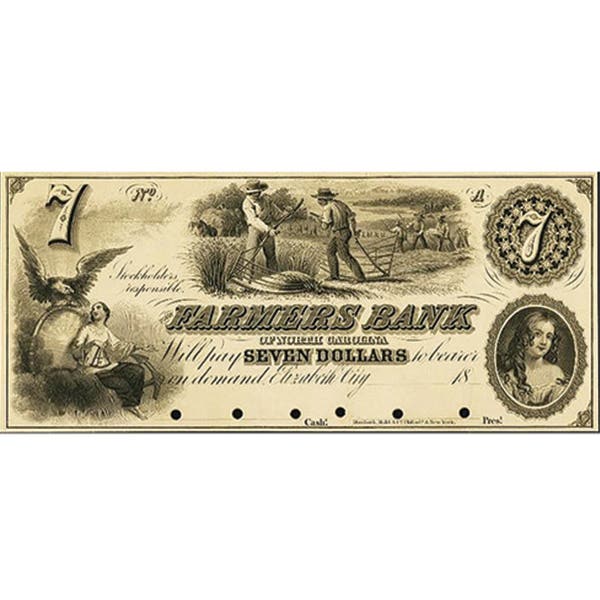

A typical example of returned 1-1-1-2 sheets involved The Wyoming National Bank of Laramie City, Wyoming Territory (2110), which received 1,000 Original Series 1-1-1-2 sheets from the Comptroller between May 29, 1876, and August 15, 1878. They were from a June 1873 printing of 1,500 sheets for the bank that were made without charter numbers. None had been shipped before passage of the 1874 act, so charter numbers were overprinted on them afterward. The note shown here was in the last shipment to the bank that contained sheets 901 to 1000.

Notice from the Laramie note that the only space for the added charter number was below the Treasury seal.

In the meantime, new 1-1-1-2 sheets continued to be turned out with the charter number above the seal. The earliest reported of them is a $1 Wickford, Rhode Island, charter 1592, bearing serials D869455-3326-B from the second of two 1-1-1-2 deliveries to the Comptroller on May 12, 1874. The first delivery that day was for Bennington, Vermont (130), beginning with serial D868980-1601, which may represent the first printing with a charter number over the seal.

Production of new $1s and $2s continued with charter numbers above the seal for a month after passage of the Act of June 20, 1874. However, the return of the old sheets to the BEP set up a conundrum because the numbers had to be placed below the seals. The inconsistency was resolved by moving the charter numbers on new sheets below the seals.

The first of the new sheets with numbers below the seal was received from the Bureau on July 28, 1874. A note from the second of two 1-1-1-2 shipments that arrived that day has been observed, a $2 from Cumberland, Rhode Island (1404), with serial D949842-2583-A. The first delivery that day was for The National Bank of Waterville, New York (1361), beginning with serial D949160-2201, which probably also has the number below the seal.

The range of Treasury serials with the charter number above the seal appears to be D868980 to D949159, encompassing 80,180 sheets for 65 banks in 22 states. Not all were issued.

If you happen to have an Original Series $1 or $2 with charter number above the seal that stretches this range, by all means send me a scan at peterhuntoon@outlook.com so I can refine this article.

The driver for all of this was the removal of soiled notes from circulation. Here is that story:

The National Bank Acts of February 25, 1863, and June 3, 1864, provided for a cumbersome procedure for the redemption of National Bank Notes. It placed the burden and cost squarely on bankers to do the job. Of course, the bankers responded by simply shoving the filthy notes back across their counters and thus avoided dealing with the problem. The grade of the notes in circulation became increasingly more wretched.

Here is how the pre-1874 system worked. All national banks, except those in reserve cities, were required to maintain cash reserves equal to 15 percent of the combined totals of their circulation and deposits. The purposes for these reserves were twofold: to provide money that would (1) allow the bankers to redeem their notes and (2) allow depositors to withdraw money from their deposit accounts. The reserves consisted of legal tender notes. The bankers could use these funds to cull worn notes from circulation and send them in for redemption and replacement.

The 1864 law also specified that 3/5ths of the 15 percent reserve could be deposited in reserve accounts in national banks located in a reserve city. These special accounts served as redemption accounts that the reserve city bankers could use to redeem notes issued by the depositor bank. The reserve city bankers could use those funds to cull worn notes from circulation and send them in for redemption and replacement.

The reserve cities designated by the law were Albany, Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, Leavenworth, Louisville, Milwaukee, New Orleans, New York, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Saint Louis, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C. The Comptroller of the Currency could add Charleston and Richmond to this list at a later date provided the “condition of the southern states will warrant it” as they recovered from the Civil War.

National banks in the reserve cities were required to hold legal money reserves totaling 25 percent of their circulation and deposits. Half of their reserves could be placed in reserve accounts in national banks located in New York. Thus, the New York bank would serve as redemption agent for notes issued by the reserve city bank. The New York bankers could use those funds to cull the worn notes and send them in for redemption and replacement.

The job and cost of removing unfit notes from circulation was placed squarely on the banks through this convoluted arrangement. This included, of course, the sorting and record keeping that attended the task before the notes were sent to the Treasurer for destruction and replacement in the case of active banks, or destruction in the case of failed or liquidated banks.

However, there was nothing in the law that required that bankers cull unfit notes from circulation, so they didn’t.

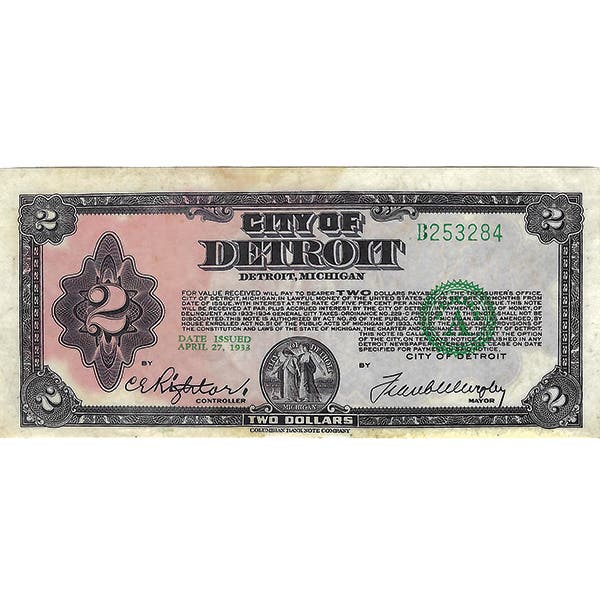

The amendment to the National Bank Act passed June 20, 1874, did away with the reserve requirements on circulation. In its place, each national bank had to deposit lawful money with the U.S. Treasurer equaling five percent of its outstanding circulation. This five percent redemption fund was to be used by the Treasurer to redeem notes issued by the bank and provide for their replacement with fit or new notes. Thus, the burden for removing unfit national bank notes from circulation landed squarely on the U.S. Treasurer. The Treasurer established the National Bank Redemption Agency in his office to do the job.

Now that the U.S. Treasury, instead of the banks, had to sort all those National Bank Notes, the government decided to make its sorting job easier. Thus, Section 5 of the 1874 amendment required the overprinting of charter numbers on all future National Bank Notes shipped by the Comptroller of the Currency in order to aid the sorting effort.

The work beginning in July 1874 performed by the National Bank Redemption Agency was staggering. Annual redemptions previously hit $36 million for the year ending Oct. 31, 1873, most of which consisted of worn notes replaced with new. That number rocketed to $137 million in 1875, an amount that represented 40 percent of the outstanding circulation during that year (Comptroller of the Currency, 1875, p. xxxvii). Exceptionally heavy turnover continued through 1878 until the problem of unfit currency in circulation was resolved.

The Comptroller of the Currency (1875, p. xxxv) reported the following faulty but interesting statistic: “The amount of national-bank notes now outstanding upon which the charter-number has been printed, is $156,256,347, leaving $101,960,555 of notes in circulation without numbers.”

These numbers do not add up to the total outstanding circulation of over $343 million reported for 1875. However, assuming that the $156 million figure is correct, well over 45 percent of the Original Series notes in circulation in 1875 already had charter numbers. This ratio could only increase with time, because overprinted Original Series notes continued to be issued for years afterward. Thus, you can see why Original Series notes with charter numbers are rather common.

References Cited and Sources of Data

Comptroller of the Currency, 1863-1912, Receipts of national bank currency from the engravers: Record Group 101, U. S. National Archives, College Park, MD.

Comptroller of the Currency, 1863-1935, National currency and bond ledgers: Record Group 101, U. S. National Archives, College Park, MD.

Comptroller of the Currency, 1875, Annual report of the Comptroller of the Currency to the First Session of the Forty-Fourth Congress of the United States: Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, LXVI plus appendices.

United States Statutes, Acts of February 25, 1863, June 3, 1864, and June 20, 1874, pertaining to national banks: Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Walcutt, Doug, 1995, Varieties of national bank notes, part 3: The Rag Picker, Paper Money Collectors of Michigan, v. 30, no. 3, p. 14-30.

Walcutt, Doug, 2001, Varieties of national bank notes, part 3a: The Rag Picker, Paper Money Collectors of Michigan, v. 35, no. 4, p. 13-26.

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

If you like what you've read here, we invite you to visit our online bookstore to learn more about Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, General Issues.

NumismaticNews.net is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com and affiliated websites.