Low Numbers on Large Size Federal Currency Caused Bottleneck

By Peter Huntoon, Doug Murray, Shawn Hewitt Before the invention of leading zeros as placeholders for numbering small size currency, the handling of low serial numbers was a serious bottleneck…

By Peter Huntoon, Doug Murray, Shawn Hewitt

Before the invention of leading zeros as placeholders for numbering small size currency, the handling of low serial numbers was a serious bottleneck in the numbering of currency at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

Serial numbering U.S. currency was considered to be an important check on runaway printing of currency by a reckless government as well as a convenient accounting device. Consequently, huge investments in labor and machines were and continue to be made to print a unique number on every note.

Up until 1903, all serial numbers were applied to currency on paging machines operated by women. The machines stamped the numbers onto currency in sheet form one number at a time. Think about this burden. In 1900, the BEP cranked out 100 million pieces of currency. By 1910 that volume ballooned to 300 million. It took a small army of women to operate those paging machines. Once numbered, the sheets of Treasury currency—legal tender notes, silver certificates, gold certificates—were sent to the Treasury for sealing and separating.

In 1903, 4-subject rotary numbering presses made by the Potter Printing Press Company were put into production. The Treasury currency numbered on those machines also was sent to the Treasury Department in sheet form for sealing and separating.

A major advance came in 1910 when the numbering of Treasury currency was switched to 4-subject machines built by the Harris Automatic Press Company. The Harris presses not only numbered and sealed the sheets, but also separated the notes and collated them in serial number order. At this point, the Treasury received fully completed notes and dismantled its sealing and separating operation.

Well, what about the low serial numbers?

The information available to us reveals that the Potter and Harris presses numbered from high to low in a given numbering run. When numbers of less than 10,000,000 had to be applied, the numbering heads in the numbering presses had to be modified to handle 7 digits. This involved removing a numeral wheel from the numbering heads in all eight positions. Sometime later during the Harris press era, the operator manually removed the block letters from the leading character wheels and inserting them into the next wheels to the right.

Either scenario was a productivity-killing proposition.

Every time the serial numbers dropped by an order of magnitude, the same laborious retooling had to be undertaken, each time at a shorter interval. You can imagine how everyone from the people operating the presses to Bureau management appreciated this.

When they got down to serials 1000 to 1, they were looking forward to going through this hassle three times for only 250 sheets. That was a no-go.

From the outset when the Potter presses came online in 1903, the decision was made to number the first 250 sheets on the old paging machines. Although laborious, it was quicker than fooling three times with the eight numbering heads on the rotary presses.

This practice was followed for the next 24 years for just about all the Treasury currency numbering runs.

In 1927, Alvin Hall, the then current BEP director, had had enough. Hall was from an accounting background and relentlessly pursued efficiency. He proposed to his Treasury superiors that the simple solution to removing this bottleneck was to do away with the first 10,000,000 serial numbers and start numbering at 10,000,001. All the notes still would have a unique serial number and the accounting would remain simple, so why bother with the manufacturing hassle of the low serials?

His Treasury superiors quickly agreed. That was the end of serial numbers 1 to ten million, not only on SCs, LTs and GCs, but also FRNs for the duration of the large note era.

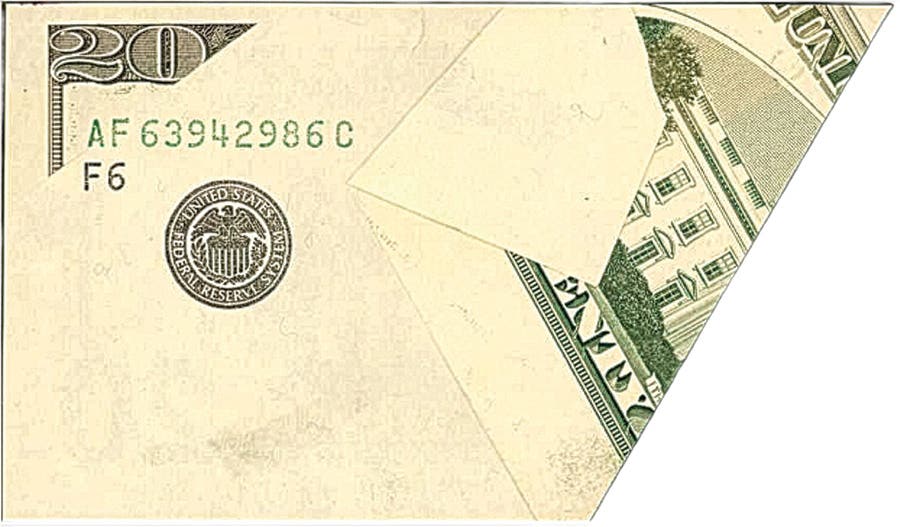

The low number notes printed on the paging machines have a distinctive appearance peculiar unto themselves. The women who applied them tended to center them in the spaces provided. The two numbers were identical because they were applied from the same numbering head. That is, the characters were the same, the spacings and alignments between the respective characters were the same, and if flaws of any type were present, both numbers had them as well. Often, but not always, the numbers were tilted slightly relative to their surroundings belying their origins at human hands. Also, when groups of consecutive numbers are found either on sheets or singly, close comparisons reveal that the numbers tend to wander a bit in the spaces provided for them.

Particularly interesting are comparisons between the first thousand serials and those that followed. The higher numbers are right justified in the spaces provided because the positions of the numbering heads were fixed in the machines with the suffix letter at the far right.

The same issue plagued the Federal Reserve Notes that begun to come along in 1914, as well as the Federal Reserve Bank Notes following in 1915 and 1918. The low numbers on them were handled the same way even through they were numbered at least initially in a section reserved for bank currency. The look of the low numbered red seal Federal Reserve notes is the same as the Treasury currencies.

Things changed shortly after the Series of 1918 Federal Reserve Bank Notes arrived. Even the low numbers were numbered on the Harris machines. Consequently, the low Harris numbers looked radically different because they were right justified.

Those first FRBN Harris numbering runs were carried out sometime in 1918. Clearly, the bank currencies were being treated differently than the Treasury currencies in those days.

We discovered one instance among the Treasury currencies where the low numbers were numbered on a Harris press. This finding involved the EA block in the $1 Series of 1899 Elliott-Burke silver certificates, a situation brought to our attention by William Baeder Jr. of USA Rare Currency. Those notes were numbered in June 1921.

His father, William Sr., had seen a cut sheet consisting of notes from the third sheet in the block go by long ago. Next, Harry Jones sold him the E9A note from that sheet. The serial numbers were doubled on it, the first of which were erased. He and his son succeeded in reconstructing that sheet by acquiring E10A, E11A and E12A as those notes came back on the market.

Shawn Hewitt pointed out that the last sheet with 2-digit numbers was 9-10-11-12 before the press operator had to retool to print the final two 1-digit sheets. Shawn figured the press operator simply let the machine print the 9-10-11-12 sheet, thereby getting 3/4ths of the job done, then pulled it, erased whatever 4-character mess had landed on the two E9A positions and had E9A stamped in their place on a paging machine.

The giveaway that this run was from a Harris press is two-fold. Most obvious is that the numbers were right-justified in the spaces for the serial numbers just as on the Series of 1918 FRBNs. The FRBNs had been numbered in 1918 so there was precedent for doing that work on a Harris press.

The second line of evidence comes from another observation by Hewitt. To the left and slightly below the left E10A and E11A serial numbers are curious faint blue tick marks, the same blue as the serial numbers. They are stray marks picked up from the numbering heads where characters had been removed from character wheels.

Shawn found a 1909 patent by B.B. Conrad, F. Sander & F.W. Wright for numeral wheels with one position designed to hold a removable character. This allowed the operator to move the prefix letters to the right for successively smaller serial numbers. As the numbers got smaller, there was nothing in the slots that held the characters that has been removed. You can see on the diagram that the raised edges of the empty slot offer two sharp highs that could easily get inked and print the ticks.

The same ticks are common on low numbered notes in the Series of 1918 FRBNs.

We have no idea whether the Conrad-Sander-Wright wheels were licensed for use in the Harris presses. If not them, similar wheels clearly were. Even with snap-in removable characters, dealing with them as serial numbers got smaller remained a productivity killer.

The person who came up with leading zeros for the small size notes had a flash of genius. We’d like to know who it was.