Long ‘s’ used on several notes

By Peter Huntoon Reader Nick Bruyer brought the fact that he had acquired an ace on which a long “s” was used in the abbreviation for Massachusetts from The Shelburne…

By Peter Huntoon

Reader Nick Bruyer brought the fact that he had acquired an ace on which a long “s” was used in the abbreviation for Massachusetts from The Shelburne Falls National Bank, charter 1144.

The long s “ſ” — which looks like a lowercase f without the crossbar — is an archaic form of a lowercase s. It formerly was used where the letter s occurred in the beginning or middle of a word, such as “ſinfulneſs” for “sinfulness.” A double s in the middle of a word also was written with a long s followed by a short s, such as “Miſsiſsippi” for “Mississippi.”

The long s was derived from the old Roman lowercase s. It fell out of use in English and American professional printing well before the middle of the 19th century, although it lingered in handwriting into the second half of the century.

It appeared in the postal location written in script within the title block opposite to the plate date. He viewed it as an anomaly because the long s had ceased to be used in the printing trades before the National Bank Note era.

I was caught flatfooted by his observation. Frankly, I had seen long ſs go by on proofs from Massachusetts, but for some reason they didn’t cause a neuron to fire in my brain to alert me that this was a variety that deserved a bit of attention. This was especially bothersome because I pride myself on having meticulously documented the exact titles used on National Bank Notes from every issuing bank in the country.

Chagrinned, I immediately pulled up the scans of the aces from David Bowers collection that he had generously sent years ago to see if there were others. His collection was particularly rich in Massachusetts aces, which was no surprise because so many banks in the state used them. I found five with the Maſs abbreviation out of the 89 banks in his sample.

Obviously, they weren’t common, but the form was used occasionally on early nationals.

I next pulled up the scans of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing proofs for Massachusetts available on the National Numismatic Collection website to determine if there was usage of the long s on denominations other than $1s. Also, I wanted to determine if it was used in the Series of 1882.

This search, although far from comprehensive, was rewarded with hits for all denominations except the $2, $5, $500 and $1,000 denominations. As for the $5s, no state or its abbreviation was ever used in the postal locations on those notes.

Of particular interest to me was that The Kidder National Gold Bank of Boston didn’t have the variety on any of the notes printed for it; specifically, $50, $100, $500 and $1,000 Original Series notes.

There were some very interesting situations lurking in the proofs.

The most interesting is that I never found a long s on a $2, even when they occurred on the $1s on the same plate.

The long s was used on the same plate combination on both the Orig/1875 and 1882 plates for some banks. In contrast, it occurred only on an Orig/1875 proof for others, followed by “Mass” on the 1882.

The big question is why was the obsolete form used at all. The answer probably is as simple as the fact that some people were still using the archaic form in their daily penmanship during the early National Bank Note era. I see plenty of examples in the Treasury ledger books from that era. Consequently, I suspect that the form that ended up on a given title block depended upon who wrote the plate orders or which engraver engraved the postal location on the dies used to make the plates.

As for carryover to the Series of 1882 plates, in some case the roll used to lay-in the postal location on 1882 plates was the same as used to make the Orig/1875 plates. You can rest assured that the siderographers who laid in the plates could have cared less which form was used. Certainly no one inspecting the plates during the certification process was concerned either.

Massachusetts wasn’t the only state with a double s. There also was Missouri and Mississippi. I looked at the early proofs for those states as well, but didn’t find any with a long s abbreviation.

At least the Massachusetts collectors have these curiosities to collect.

As for me, the last thing in the world I ever expected to learn or worry about was an esoteric nuance like the origin and use of the long s in the English language. This is the wonder and benefit of collecting national bank notes. Mixing with people such as Nick Bruyer, who possess entirely different educations, interests and observational skills, opens such doors.

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

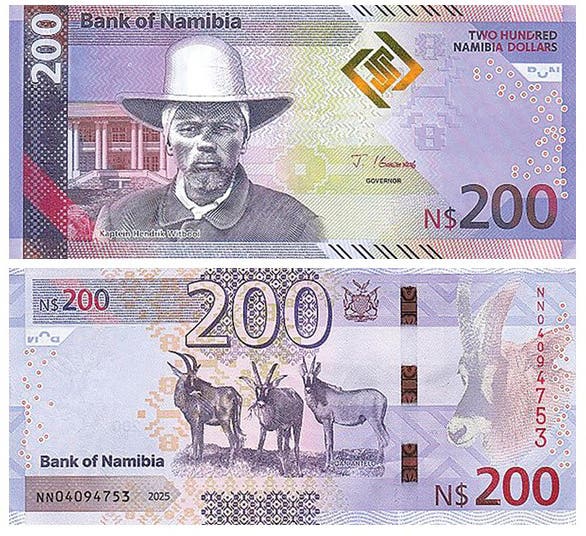

• Order the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, General Issues to learn about circulating paper money from 14th century China to the mid 20th century.

• With nearly 24,000 listings and over 14,000 illustrations, the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, Modern Issues is your go-to guide for modern bank notes.