Current Territorial NBN Roundup for 2022

The yearly average count of 13 new-to-the-census territorial nationals since such counts began in 1989 isn’t close to being realized in 2022. Only five such territorials have been reported so…

The yearly average count of 13 new-to-the-census territorial nationals since such counts began in 1989 isn’t close to being realized in 2022. Only five such territorials have been reported so far,

Those counts dropped to 4 per year during the COVID pandemic. Is the fall off of coin shows due to COVID to blame or is the supply of territorials out in the weeds falling off?

The interesting thing about this year’s crop so far is that it consists of a significant mix; specifically, two serial number 1s and no Honolulu’s. Honolulu’s usually dominate additions. Here is what we have so far.

Probably the one representing the most fun is the $5 1875 from The Colorado National Bank of Denver. After The First National Bank of Honolulu (5550), this bank and The Deseret National Bank of Salt Lake City (2059) are tied for the second most reported territorials at 34 each. The thing that made this note so much fun was that it was offered on eBay with buy-it-now price of $429.99 with free shipping along with this quote: “Was stored flat out of light for nearly 100 years by a late relative who was in banking all his life.”

The note most people would place at the top of this list obviously is the Original Series $2 from the Deseret National Bank of Salt Lake City. This spectacular note is the third territorial reported from the number 1 sheet, the other two being $1s from the B and C plate positions. I grant you, that it truly is hard to beat a number 1 deuce. It carries the ever-popular Brigham Young signature, the then leader of the Morman church. I highly suspect that this jewel, although new to the census, is from an old numismatic collection that had never been logged into the census database. Regardless, it is going to create a big stir when it is hammered down.

It joins the elite club of number 1 territorial deuces. The others are from The First National Banks of Denver (1016) and Santa Fe (1750). It appears that they are starting to become common!

Incidentally, there is only one Series of 1875 deuce in the territorial census, a number 2361 from The City National Bank of Denver (1955). In contrast, there are a total of 16 Original Series deuces.

The new Phoenix $10 brown back is a rather low-grade work-a-day specimen from the Territory’s most prolific brown back issuer. It was shipped to the bank from Washington on August 11, 1896 and pen signed by president F. S. Belcher and cashier C. J. Hall. Territory of Arizona notes are tough to acquire so the appearance of this note had to make some collector very happy.

The thought of a Custer City number 1 red seal $20 does take one’s breath away. It’s the second red seal territorial to turn up on the bank, the other a $10 with bank sheet serial 88. Custer City is a great town name and, of course, was named in honor of U.S. Army Lieutenant Colonel George Custer. Custer had distinguished himself in the Civil War but later on June 25, 1876 during the Great Sioux War he led his men of the 7th Cavalry Regiment and himself to their deaths against the combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes in the Battle of the Little Bighorn River in Montana Territory.

Originally, Custer City, which lies 90 miles west of Oklahoma City, was called Graves with a post office established with that name there on Jan. 22, 1894. Phillip Graves was one of the original boomers who staked a claim on that land and served as the postmaster from his own dugout home. The name of the post office was changed to Custer City in September 1904.

To fully understand the founding of the town, we have to roll back history to when the land there was ceded by treaty to the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes.

The Creek and Seminole tribes were forcibly relocated from the southeastern states to Oklahoma in the 1820s and 1830s. However, the Reconstruction Treaties of 1866 took their western Oklahoma lands away as retribution for their support of the Confederacy during the Civil War. Next, in 1869 as Colorado became overrun by colonizers, the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes from Colorado were resettled in their place.

The Dawes General Allotment Act of Feb. 8, 1887 imposed the concept of land ownership on the members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes whereby set per capita acreages were allotted to each from what formally was collectively owned tribal land within their reservations. Once the distribution was affected, title to the parcels passed to the individuals and the individuals were deemed citizens of the United States as distinguished from being citizens of a sovereign indigenous nation.

The effect was to subdivide the reservations and terminate the association of the individual with his tribe. The Secretary of the Interior was authorized to negotiate with the tribe for the purchase and release of the unallotted lands that then would be opened to homesteading. In the meantime, Oklahoma Territory was established on May 2, 1890, which encompassed what would become Custer City.

The following is stitched together from web articles by Wilson and Reggio writing for The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

Some 3,500,000 acres of the Cheyenne and Arapaho land was thus opened to homesteading in Oklahoma Territory through a proclamation signed by President Benjamin Harrison on April 12, 1892. That opening resulted in the third great land rush in Oklahoma, an event scheduled only a week in advance for April 19, in order to limit the number of people who could travel there to participate. Some 25,000 showed up, among them was Phillip Graves.

The boomers lined up to await the noon signal that would initiate the rush. People had arrived in every conceivable conveyance—wagons and buckboards, large, horse-drawn buses loaded with settlers, small houses on wheels being pulled by six-horse teams. A Kentucky thoroughbred with jockey awaited. A hot air balloon was being readied. Fort Reno soldiers pushed the surging crowds back to the line until a cannon roared at noon releasing the mob. Six horses strained against their collars inching a frame house across the line to a claim. Some settlers ran a few steps and quickly planted their stakes, while others ran over a mile. Fast horsemen rushed toward lakes but found only desert mirages. The Kentucky thoroughbred became so agitated, he turned and stampeded in the wrong direction. One girl fell and broke her leg. No one stopped, but everyone conceded her the claim on which she lay incapacitated.

Because sooners—squatters who illegally entered and staked out claims on the best land prior to the land rush— shunned this land rush, the boomers had time to select the best land more carefully. What most got was a 160-acre piece of western Oklahoma, a generally desolate plot largely without water and very poorly suited for row crops. This contrasted to the Indian Territorial lands to the east where rain was more plentiful.

The fact was, most of the land was suitable only as range cattle country and the budding ranch crowd knew it so they and their employees penetrated deeply by horse to claim whatever springs and streams they could find. Following the rush, they gradually began to consolidate ranches, assembled from boomers who found faming to be untenable. Relinquishments sold for as little as five dollars.

When the dust settled, over 2.8 million acres lay unclaimed, about four-fifths of the land offered. The eastern part contained much unclaimed land, but the western part was practically uninhabited. As of June 30, 1892, Territorial Governor Abraham J. Seay estimated that only 7,600 settlers lived on the land. Even in 1899, historian Edward Everett Dale said that one could ride west the whole day without seeing a homestead.

The townsite of Graves/Custer City was opened for settlement in July 1902 when the Frisco Townsite Company sold lots. The land for the town had been bought from local homesteaders Phillip Graves, A. B. Oberly and Jay Hamilton. The Blackwell, Enid and Southwestern Railroad constructed a line that connected the town with Darrow to the northeast and the Red River to the south between 1901 and 1903. This solidified the future of the town.

The railroad bypassed the nearby community of Independence, so its citizens moved to Custer City. In 1902 Everett Veatch, who had published the Independence Courier newspaper, moved to Custer City and established the weekly Custer Courier. The Custer City Telephone Company was granted a charter in September 1902 and soon ten miles of telephone lines were installed. The town had electricity by 1912.

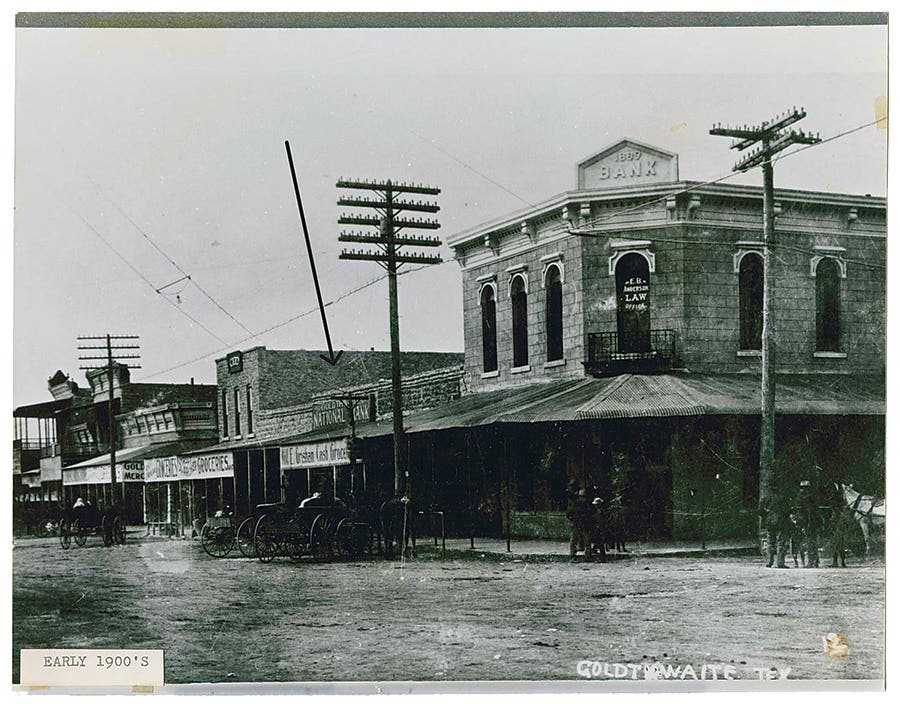

Custer City served as a support and trade center for a surrounding agricultural region in which wheat, broomcorn and cotton were grown. By 1909, the town had two banks including The First National, four general stores, four elevators, a flour mill, a cotton gin, a broomcorn factory, three liveries, three blacksmith shops, a tinsmith and a wagon maker.

At statehood in 1907, Custer City had a population of 552. It peaked at 854 in 1910, only to decline to 671 in 1920. The population slowly dwindled to 375 by 2010.

The First National Bank was organized May 15, 1907, chartered June 4, 1907, and survived beyond the end of the national bank note era in 1935. The bankers maintained a small circulation of $12,500 from its organization through 1912, The circulation was doubled to $25,000 from 1913 to 1935.

I learned that the Custer City note actually arrived on the numismatic scene in 2016 as an attractive mid-grade specimen with rubber-stamped signatures of president O. E. McCartney and cashier Leon L. Hoyt. McCartney’s signature was strong; Hoyt’s a bit imperfectly applied or faded. The signatures are now ghosts of their former selves.

The first I learned of it was when it was offered during October 2022 on the Liveauctioneers website, a collectables website featuring numismatic and philatelic items. Clearly the seller had stars in his eyes because the sale estimate was $150,000 to $250,000.

Of the five territorials to turn up so far this year, the one that resonates the most with me is the Tucumcari. My infatuation with it is twofold. First, it is the discovery territorial note for the bank, always something that comes as a thrill. Second, the town name is unusual and quintessential New Mexican. Tucumcari is located on the eastern plains of New Mexico, 40 miles west off the Texas line.

New Mexico was admitted as a state on Jan. 6, 1912, so it had a long territorial issuing history. Many of its territorial banks were organized after 1900. The Tucumcari bank was young, having been organized March 31, 1902 and chartered June 4th as the successor to the Exchange Bank.

The First National was liquidated May 8, 1934, quickly followed by The American National Bank on May 15. They were succeeded by The First-American National Bank in Tucumcari, charter 14081, a successor to the two having been chartered March 17, 1934. The new bank represented a marriage imposed by the Comptroller of the Currency in order to strengthen national banking in Tucumcari during the Great Depression. The management team from The First National served in the First-American National.

The First National Bank began its territorial existence in 1902 as a minimally capitalized bank with a circulation of only $6,250 as allowed by the Gold Standard Act of 1900. The capital was increased substantially in 1907 allowing the bankers to increase their circulation to $50,000, a number that held for the rest of the territorial era.

The bankers circulated sufficient numbers of Series of 1902 red seal and date back territorial notes that I considered the appearance of the one this year to be long overdue. The note that finally appeared is a 1902 date back that was printed in the spring of 1910. If you could read the rubber-stamped signatures, they would be cashier Earl George and most likely president H. B. Jones. Jones’ predecessor, W. F. Buchanan, who left office during 1910, probably was gone by the time the note reached the bank.

The following information concerning the naming of Tucumcari and its history is largely taken directly from Whittington with selected facts gleaned from the other two Tucumcari websites that are cited.

The town of Tucumcari, like the bank, was organized after the turn of the 20th century. Its name was derived from Tucumcari Mesa south of town.

The origin of the word Tucumcari is uncertain, as is typical of location names ostensibly translated from Native American words. The most popularly cited origin is that Tucumcari is derived from the Comanche word “tukanukaru,” meaning “to lie in wait for something to approach.” The flat-topped mesa served as a lookout for Comanche raiders preying on cowboys driving cattle along the Chisolm and Comanchero Trails during the mid-19th century.

Alternatively, a 1777 burial record mentions a Comanche woman and her child captured in a battle at Cuchuncari, which is believed to be an early version of Tucumcari. Other translations include “squatty mountain,” “place of the buffalo hunt,” and “mother’s breast.”

The ambiguity comes from different people asking different Native Americans in different decades what the word meant. Owing to vagaries attending translating it was unclear to the person being asked if the question was the meaning off the word, what happened at the place of that name or some other linguistic nuance. As elsewhere, this problem affects a large number of New Mexican place names. The reality is that Tucumcari is a great word that really sounds New Mexican, so people love it.

The town of Tucumcari owes its origin to a snowstorm in 1900 that stranded some railroad officials at Liberty, three miles to the north. The men found refuge at the Goldenberg home there for three weeks.

They offered to pay for their room and board as they prepared to leave, but the Goldenberg’s refused payment. The grateful men revealed to the family that the railroad would be going through and would establish a shop four miles from the Goldenberg home.

In November 1901, A.D. Goldenberg, his brother Max, J.A. Street and partner Lee Kewen Smith each filed on 160 acres between the Canadian River and Tucumcari Mesa to the south certain that the railroad would have to cross their land. They formed the Tucumcari Town Site and Investment Company, each contributing part of his land to the venture. That area was surveyed as a townsite as the Rock Island Railroad laid track through the area.

Alex Street put up the first tent on the townsite in October 1901. Street & Smith began selling whiskey to the railroad workmen. Max Goldenberg built a new home completed in December 1901 that served as a store, hotel and post office. By January 1902, several new businessmen hurriedly put-up buildings. The town’s first newspaper The Pathfinder began publishing in February 1902.

Tucumcari nearly doubled in size by the end of 1903 with a population of close to 1,000. Two million acres of land was opened in the area for homesteading, so settlers arrived allowing Tucumcari to boom between 1910 and 1920. Tucumcari experienced growth even during the depression years. It faced a housing shortage after World War II as servicemen returned home to former jobs or to start new businesses.

For decades, Tucumcari has been a priority stop for cross-country highway buffs plying U.S. 66—the Mother Road—that was laid out through town in 1926. The old 66 route is now supplanted by Interstate 40. Tucumcari is the largest town on the highway between Amarillo, Texas 115 miles to the east and Albuquerque, New Mexico 175 miles to the west.

U.S. 54, one of the major strategic diagonal U.S. highways, begins at the Mexican border at El Paso and serves as northeast-southwest corridor through Wichita, Kansas and the heartland beyond. It too passes through Tucumcari and although not as famous as U.S. 66, it is equally significant.

Which of the five new territorials to show up so far this year is your pick for territorial of the year? What criteria drives your choice? These five newbies may not be the end of the territorial story for 2022 because we have a couple of months to go.

Heritage Auctions just held a remarkable sale October 5-7 at Long Beach wherein 18 territorial notes from six of the territories were offered. I am unaware of a larger offering this century or, for that matter, a long time before. Table 2 lists the notes in that sale. No question, 2022 was a good year for territorial collectors.

Although there were no large-size Honolulu’s in the October 5-7 Heritage offering, five will be forthcoming in their fun sale, all previously reported notes.

The National Currency Foundation census of territorial note now stands at 1,177.

Sources