Boggs blurred lines between art and money

Editor’s Note: This article is Part I of a two-part study of James Stephen George Boggs, the internationally famous money artist who died at age 62 in late January of…

Editor's Note: This article is Part I of a two-part study of James Stephen George Boggs, the internationally famous money artist who died at age 62 in late January of this year. Click here to read Part II.

By Neil Shafer

We first met in the early 1990s at one of the Florida United Numismatists shows. It has been a long enough time that my exact memory of how we came together is no longer with me. I never tried to put our many encounters in my permanent memory bank because I never thought they would rise to the importance they now seem to contain.

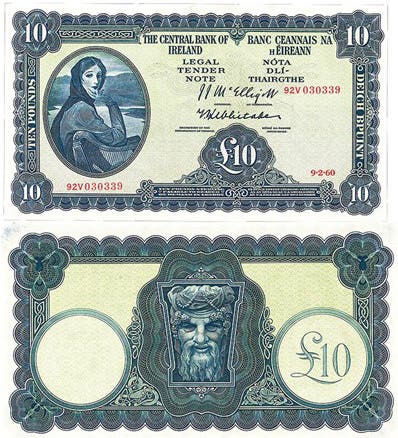

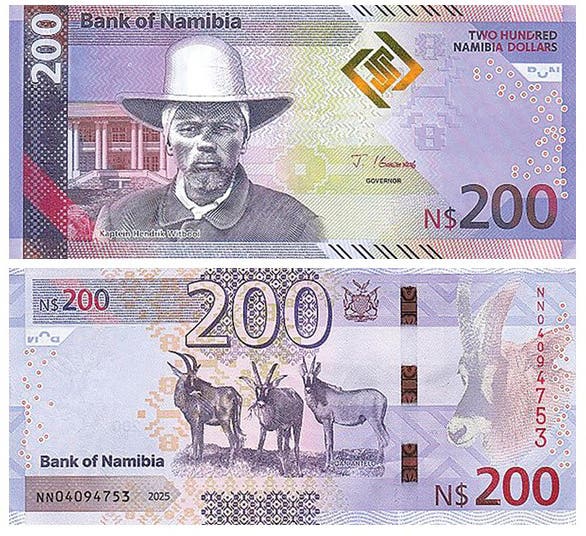

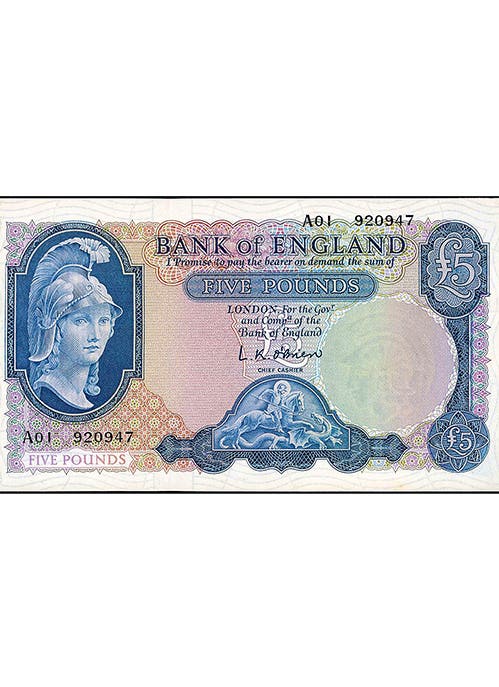

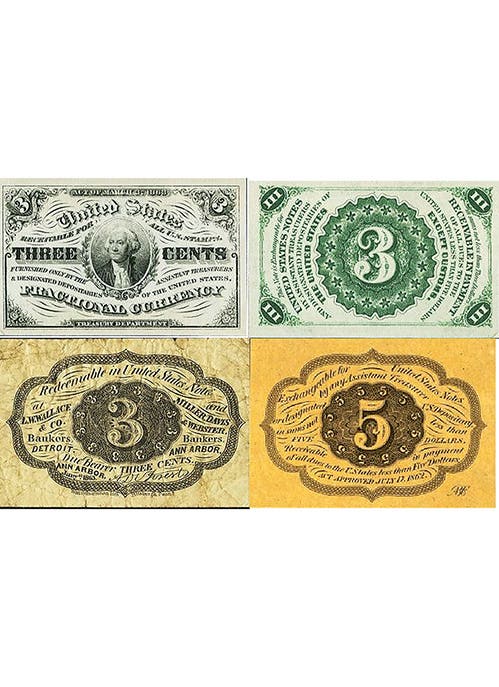

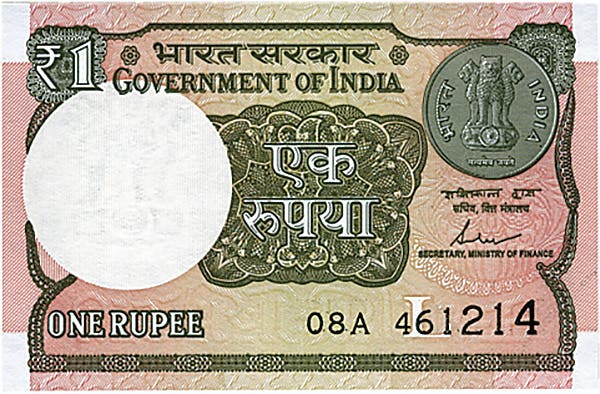

At the times we spent together I would always come away with various Boggs-produced pieces of currency art, some of which he personalized for me. You see examples of several of those items illustrated with this article.

There was no question at the shows he attended that he was a self-made sensation. He had a substantial following and an eager group of collectors willing to embark on attempting to garner a completed “transaction,” an activity I will describe in detail a bit later.

Boggs died in January of this year in Tampa at the age of only 62. He was seen at the FUN show earlier that month, in a sort of disguise. That was part of the essence of the man, always a bit of mystery surrounding his persona. His full name after becoming part of his permanent family was James Stephen George Boggs, but most folks simply called him “Boggs.” At times he referred to himself when signing his works of art as “Boggsie.” He also charged for signing his name, leaning on the supposed difference between a simple signature and an autograph. I don’t recall how much it was for the former, but for the latter it was $10.

So really, what was his spiel? What he did was create works of artistry (known in the collector realm as Boggs Bills (or sometimes Boggs Notes) that closely mimicked U.S. paper currency, then try to tender them to whomever was performing a service or giving him some kind of goods as pay for whatever it was they did. He did not call his uniface art works “money” but he placed a value on them that coincided with their “face value” when offering them as payment. It was then completely up to the potential recipient to make up his mind as to whether or not to accept such a work of art in payment. If it was, then he had to give a receipt and change to Boggs, who then annotated that receipt and change as to the exact transaction that had occurred.

At a later time Boggs then offered for sale that receipt and change, with information as to where and in what circumstances he “spent” his artistry. It was then left to the buyer to locate this artwork recipient and try to purchase the Boggs bill. If successful, then all the ingredients of a full “transaction” were in place and the work was complete.

During the 1994 ANA summer convention in Detroit, I was fortunate enough to have been able to obtain from Boggs a receipt and the $5 change he received from a taxi driver who took him from his hotel to the convention site. He informed me where he had obtained the taxi; the driver’s name was on the receipt. I then went to the area where the taxis were being assigned, and luckily enough I was able to intercept that driver. After we discussed the situation he readily agreed to let me purchase his $10 Boggs bill (I believe I offered him $50 or thereabouts) and presto! I had a completed three-piece “transaction.”

Boggs thought of a “transaction” such as this as a type of artistic performance. He never thought of himself as a counterfeiter, but in two instances outside the United States he was arrested and accused of this exact offense. In England he went on trial as a counterfeiter in 1986, as he described the situation in a presentation I found on the Internet. He said that the criterion they used was acceptance of a note by “a moron in a hurry” (and I think he included a comment about such a person being in dim light as well). He was acquitted in that instance. Another arrest took place in 1989, this time in Australia under similar circumstances; there not only was he exonerated but he was awarded the equivalent of $20,000 in damages.

In this country, while he was never brought up on charges of counterfeiting, something over 1,300 items were confiscated by the Secret Service during several raids on his premises. He spent a great deal of time and effort trying to have those pieces returned to him—all to no avail.

How, he said, could he be the object of such an accusation when his artwork notes were really looked at? In the first place, as mentioned earlier, they were all uniface; if you compared an original to a Boggs bill in many places in text and signature areas, you found differences, sometimes humorous, in abundance. On Boggs bills the two serial numbers were entirely different as well. How much more is needed before one is convinced that such pieces are, indeed, true works of an extremely talented artist.

Boggs has been the subject of a number of articles and at least one book detailing his antics while also providing him with a forum to advance his ethical and philosophical ideas about the essence of money—what it represents, what convergence art and money have. One book I have is titled Boggs A Comedy of Values, by Lawrence Weschler. Published in 1999, the author states in his Preface that “it sure can give one pause the way such serious, even scary, stakes keep getting dragged into play by the antics of our sly protagonist, the perpetually confounding money artist, J.S.G. Boggs.” This book goes into great detail about the legal difficulties Boos encountered overseas, among many other descriptions and quotes from Boggs himself about the real value of money and art. Weschler is also featured in the same Internet presentation with Boggs that I was able to locate while researching facts for these articles.

His highly unusual and extraordinary talent was discovered quite by accident, I believe in 1984. That much of the story I feel is accurate. He was in a Chicago restaurant and was idly drawing an image of the face of a $1 bill on his napkin. This part is also thought to be a true statement. But then there is a divergence. In the Boggs Internet narrative mentioned earlier, he goes on about the waitress at first not wanting to take his drawing, then she took a longer look at his artwork and expressed interest, whereupon he hit on the idea of offering it instead of a real $1 as payment for his food. As I understand it, at first she refused, then later decided to accept, but at that point he thought he wanted to retain it himself. So she offered him a higher amount and he still refused. Finally she accepted it and gave him a dime back in change. The desire to create such images had been ignited, and Boggs was on his way to a kind of fame unique in the art and numismatic worlds.

This article was originally printed in Bank Note Reporter. >> Subscribe today.

More Collecting Resources

• The Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money is the only annual guide that provides complete coverage of U.S. currency with today’s market prices.

• With nearly 24,000 listings and over 14,000 illustrations, the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money, Modern Issues is your go-to guide for modern bank notes.