Old Counterfeiting Operation Found

Seventeenth-century coin blanks found on a remote Spanish island reveals evidence of a pirate counterfeiting workshop hidden in plain sight.

No wonder pirates would raise a flag nicknamed the Jolly Roger. You’d be jolly if you could mint your money and not get caught.

The Columbretes Islands aren’t much to talk about. The islands are a group of formerly volcanic uninhabited islets off the east coast of Spain in the Gulf of Valencia. The Romans operated mints in parts of Hispania, but the Columbretes Islands weren’t among them.

The only successful human occupation of the islands began between 1856 and 1860, when a lighthouse was built. This small community operated the lighthouse and kept smugglers from using the islets as a refuge. The year 1856 is likely the islet’s only date worth remembering; that was when intentional fires were set to rid the Columbretes Islands of a poisonous snake problem.

The lighthouse was automated in 1975, resulting in the lighthouse keepers and their families abandoning the islands. In 1987, the Generalitat Valenciana of the self-governing autonomous community of Valencia installed the first surveillance services. Today, tourists travel to the islands on day trips.

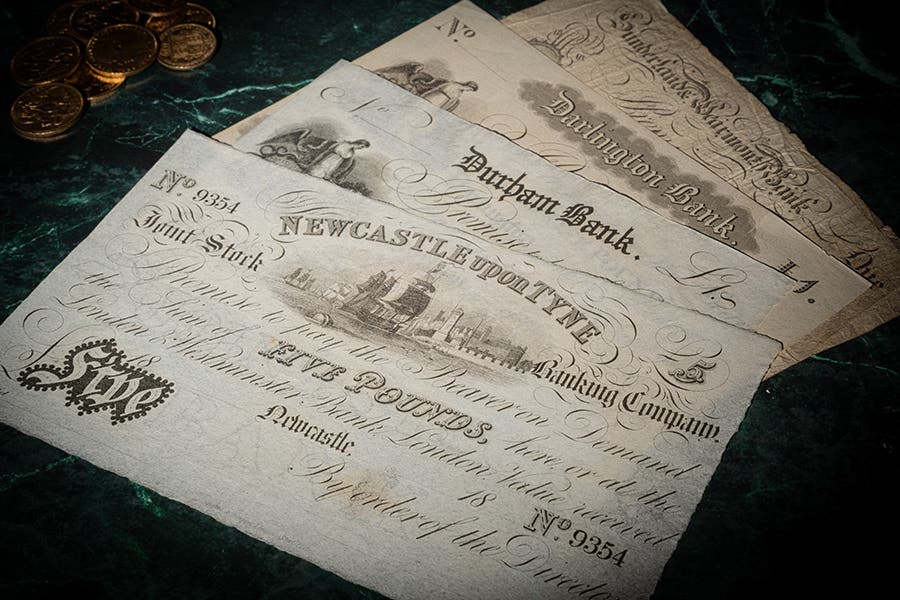

There is evidence that lighthouse keepers and tourists are not the only people who have temporarily occupied the islands. In April 2025, a maintenance worker fixing an old rainwater collection channel encountered what has since been concluded as 33 unminted coin planchets, suggesting counterfeiters (likely pirates) had left these coinage blanks behind.

The Golden Age of Piracy is generally between the 1650s and 1730s. Piracy was widespread in the North Atlantic and the Indian Ocean. The isolated Columbretes Islands were a sufficiently welcoming place to hide from authorities. The island’s proximity to Spain would also have been convenient, considering the Spanish silver 8-reales coin was a popularly used international currency.

A numismatist and archaeologist working at the natural reserve brigade first detected bronze greenish metal fragments that appeared to have been cut with shears. The worker, being sufficiently knowledgeable, was able to identify the fragments as relating to coin production.

The entire find—fragments, pieces of bars, metal scraps, and a cospell, a circular piece intended to mint a coin—was discovered near the island’s cemetery and was reported to the Museum of Fine Arts of Castellón, who later transferred the study to the Universitat de València.

The Universitat de València has since concluded that the coinage blanks likely belonged to a late 17th-century counterfeiting workshop. The university verified that although none of the pieces were minted, all were prepared to be turned into coinage. “Everything points to a small counterfeiting workshop active in the 16th or 17th century,” says Museum of Fine Arts of Castellón archaeologist Arturo Oliver Foix.

You may also like: