Facts about Fakes: Don’t Forget a Coin’s Edge

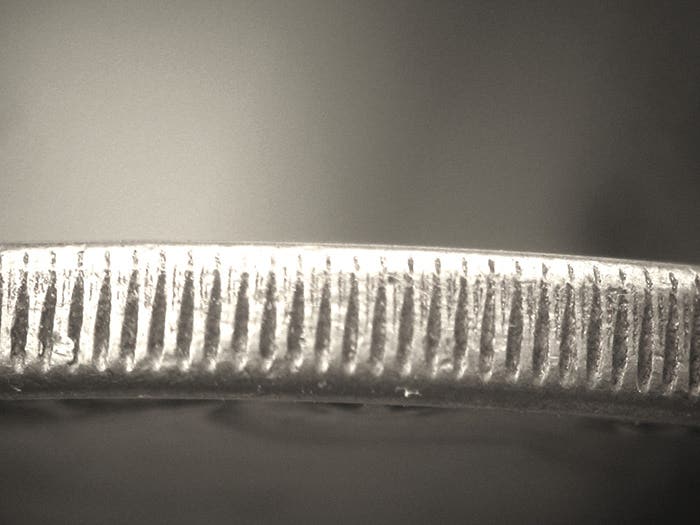

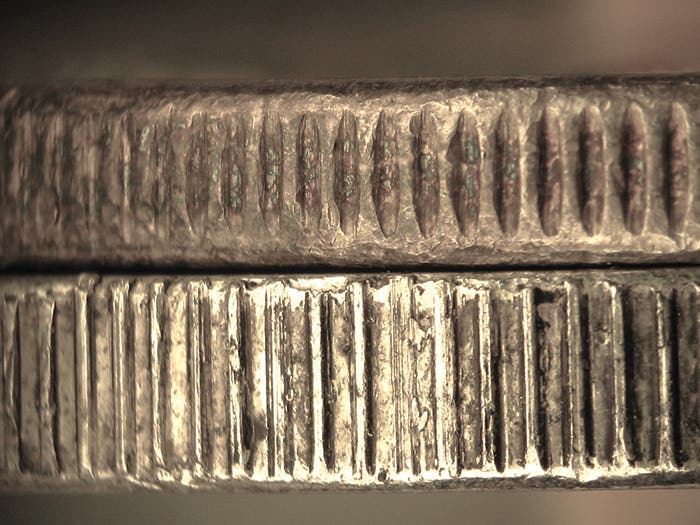

From reed counts to edge shapes, subtle details on a coin’s edge can expose counterfeits—making the third side an essential tool in authentication.

Some years ago, a numismatist (authenticator?) wrote that coins have three sides. I can assure you that this was well known to coin authenticators long before then, yet never stated in print. Back in the 1970s, I wanted to see if the edge reed count could be used to authenticate genuine five-dollar Indian gold. As I remember, it failed because both the genuine and counterfeit coins had the same reed counts. Next, I tried the same thing for 1916-D dimes. If the P-Mint coins had a different reed count, it would simplify the authentication of these commonly altered coins. Since then, both the VAM dollar reference and the Seated Liberty Half dollar book have contained charts showing the reed counts for the different dates and Mints. Presently, I’m counting the edge reeds found on Barber quarters for my diagnostic files. What seems to be the case is that in the early Twentieth Century, the reed counts for all denominations of U.S. coins became standardized with very few exceptions, such as the 1921 (wide reed) IRE Morgan dollar.

ICG, the third-party coin grading service where I work, just purchased the new reference book on Trade Dollars written by Joe Kirchgessner. This book is a classic in-depth study of the series, combined with a breakdown of the top varieties. I think of that section part of the book as a “Cherry Pickers Guide” to important Trade dollar varieties. I suggest you get a copy while it is available. In the book, there is a short section on edge reeding. As soon as I saw it, I rushed over to my diagnostic files on these coins to see what it contained. Although my diagnostic records of U.S. coins for each date and mint assembled over fifty years would form a stack over twelve feet high, my search was disappointing as I discovered few results. You see, back in the 70s and early 80s, most of the time I could tell if a Trade dollar was authentic or not with my naked eyes in the few seconds it took to bring it over to the stage of the stereo microscope I used. There was no reason to take the extra time to count the edge reeds because the mint marks on these coins were rarely added or removed. In over fifty years, I’ve seen less than a handful of these alterations on Trade dollars, as most fakes have been die-struck. Since the late 80s, the die-struck counterfeits have become so deceptive that I now often spend as much as five minutes examining a single coin and recording its dies. Unfortunately, many authenticators, under pressure to move coins through their hands, do not have this luxury.

I think a complete chart of reed counts would make a good addition to Mr. Kirchgessner’s book. It can possibly be used to help understand the relationship between the differences I found thirty years ago on the Type II (no berry) hubs. This task may be more difficult than it should be due to the large number of coins entombed in TPGS slabs. There is hope. Recently, on the Collectors Universe Message Boards, a few members are doing what one called “Playing Numismatist” in a reply to criticism from a long-time Trade dollar expert. They are counting the edge reeds of Trade Dollars! I’m not allowed to post on that forum anymore, so I cannot join in. However, I hope some collectors reading this column will add to their efforts. I know of two ways used to count a coin’s edge reeds. For one, you’ll need a camera or cell phone plus the reflector from a flashlight. When the coin is placed into the reflector, its edge will become visible from overhead, and it will appear in a photo so it can be counted. I count edge reeds under a microscope set at low power. I find a significant mark on one reed and turn the coin while counting until I reach that point on the edge again.

You may also like: