Lempke

Enough already on the “Lempke issue!” I first considered writing this two months ago but held off because I thought I had seen the last letter on the subject. Being sorely mistaken, however, here’s my 2-cents worth.

Enough already on the “Lempke issue!” I first considered writing this two months ago but held off because I thought I had seen the last letter on the subject. Being sorely mistaken, however, here’s my 2-cents worth.

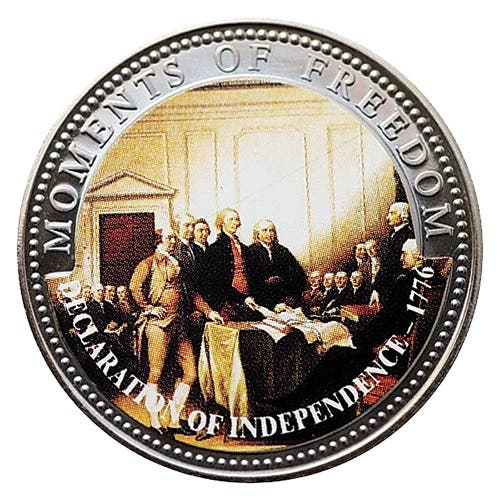

I am not normally a gambling man, but I would make two bets here: Firstly, that the bulk of the writers who have pontificated that Mr. Lempke return the coin or pay the dealer substantially more than the original, agreed-upon price, would have found some circumstance that would have warranted their keeping the coin – just like Lempke, whom they chastize.

Secondly, I’d bet that notwithstanding the fact that the dealer could have realized waaaaaaaay more profit than he did, he, nonetheless, made a good profit on the deal. To support that, I offer the following story which I fear is all too common when non-collectors sell coins to dealers.

First a little background: I live in a rural county in California’s “Gold Country” –the Sierra Nevada foothills. There is only one coin dealer in my entire county. The same is true of the adjoining, similarly rural county. A few months ago I spoke to an elderly woman who told me of her sister who recently sold a Whitman folder of Lincoln cents (Vol 1) complete, excepting only the 1922-Plain. The set had been put together by her late husband. She had no clue as to the fair market value of the coins in that folder.

She took the folder to one of the dealers who offered her $600 for the set – a price that, depending on the condition of the three keys and the teen S’s, was somewhere between a very good deal for the dealer and what some might term “outright theft.”

The sister jumped on the offer and happily pocketed the 600 bucks. Why did she so quickly accept the $600 offer? Because the day before, the other dealer made it sound like he was being very generous and screwing himself when he offered the sister 12 whole dollars for the 90 cents in pennies!

Lastly, I submit that Lempke’s dealer was content with the deal he struck with Mr. Lempke. As a practicing lawyer, I am familiar with the common principle of law that would have allowed the dealer to void the Lempke transaction had he wished to do so.

That principle is called “mutual mistake of fact.” Simply stated, the principle provides that where two parties enter into a contract, and both believe that a certain material fact exists (or doesn’t exist) and it turns out that they are wrong, the contract is voidable by either party. (Though, of course, only the “harmed” party is going to complain.)

The example taught in law school is probably several hundred years old. A man agrees to sell his cow, believing it not to be pregnant. The buyer, likewise, believes the cow not to be pregnant. They agree upon a price. It turns out, however, that the cow is pregnant, hence, worth a value far in excess of the agreed upon price. That sale is voidable by the seller should he wish to do so.

Please note that this principle does not apply where one knows the true facts and the other does not. An example of such would be where Lempke saw the rare-date Morgan in the “stock” pile and chose to buy it. That situation is perfectly legal and an example of a “shrewd, knowledgeable buyer.” That, however, is not the situation with Mr. Lempke. He told us in his first letter that he did not realize the presence of the rare-dated coin until he got home. And all writers on this topic have assumed that the dealer wasn’t aware.

From time-to-time we read of the example of the dealer at a show who has a large cent listed as “Sheldon variety such-and-such,” but the buyer recognizes it as an “NC” variety. That contract is not voidable; again, a “shrewd, knowledgeable buyer.” Of course, should the situation be reversed and the dealer tries to palm off a common variety as a rare one when he knows the difference, thatwould be “fraud.”

It is important to note the difference between a contract that is “voidable” and one that is “void.” A “voidable” contract is, and remains, valid until one party seeks to get out of it. A “void” contract is, and never was, a contract to begin with. An example of a “void” contract is a contract made with a person who does not have the mental capacity to enter into contracts or, by law, a person under the “legal age.”

Legally speaking, Lempke’s contract is valid until the dealer seeks to overturn it. And, to our knowledge, he has not sought to do so. (I think if the dealer had tried to get the coin back, Mr. Lempke would have told us in his recent Viewpoint.)

I have no doubt that Mr. Lempke’s dealer is aware of the subject transaction. Considering all the ink that has been spilled to write about that contract in the pages of this newspaper, Lempke’s dealer would have to live on another planet not to be aware.

The dealer, however, has elected not to void the sale. This leads me to strongly believe in the meritoriousness of my second bet.

Since it appears that both Lempke and the dealer are happy with the transaction, who the heck are we to insist that something different should have been done? Since the parties to the agreement are happy, we have no right to demand that Lempke refund anything.

I recognize that it is a great American pastime to stick our noses into other people’s business. The “Lempke issue,” however, is one that we have stuck our collective noses too far in already. Enough!

Michael S. Carbonaro is a 30-year attorney and 50-year collector from Sonora, Calif.

Viewpoint is a forum for the expression of opinion on a variety of numismatic subjects. The opinions expressed here are not necessarily those of Numismatic News.

To have your opinion considered for Viewpoint, write to David C. Harper, Editor, Numismatic News, 700 E. State St., Iola, WI 54990. Send e-mail to david.harper@fwmedia.com.