Matching Monetary Standards Promotes Commerce

Almost every country has its own monetary system. But, for purposes of commercial transactions, it is easier to conduct commerce in a matching monetary standard trusted by all parties to…

Almost every country has its own monetary system. But, for purposes of commercial transactions, it is easier to conduct commerce in a matching monetary standard trusted by all parties to the exchange.

In early monetary history, gold and silver were traded on the basis of weight and perceived purity. This was not as efficient as using units (coins) of standard weight and purity, which is why the Greek tetradrachm and Roman denarius became so widely used beyond their borders.

Lands neighboring Greece and Rome’s domains often copied the metallic standards of those coins in order to make them more acceptable in trade. After the fall of the Roman Empire, few coins were struck in western Europe, usually of lower purity and precious metal weight, while the Byzantine Empire maintained standard coinage.

In France, King Pepin the Short (752-768 A.D.) introduced a silver denier in 755 A.D. The purity was high, as was the quality of production. Shortly thereafter, the silver penny debuted in England, probably during the reign of King Offa of Mercia (757-796 A.D.) of virtual identical weight and purity. Both weighed about 20 grains. The term “denier” was derived from the Roman denarius as was the “d” symbol for the British penny.

For 500 years after its debut, the British penny was the dominant, and often only, denomination struck in England. It was so popular that it circulated throughout Europe. It served as a model for coins of virtually matching silver content struck in Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Germany and Poland. In fact, the first king of Poland, Boleslaw I (1024-1025), issued coins bearing the name of English King Aethelred I of Wessex (865-871).

The gold dinar (again with a name derived from the denarius) circulated from Spain to central Asia in the Islamic world once it debuted circa 696-697 A.D. under Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan (685-705) of the Umayyad Caliphate.

The major Italian trade city of Venice came out with the grosso in 1193, a coin weighing 2.18 grams of 98.5 percent pure silver. These coins contained far more silver than the pennies and deniers, making it easier to use them in trade with the Byzantine and Islamic lands.

In 1252, the Italian cities of Florence and Genoa introduced gold coins weighing 3.5 grams with a gold purity of 98.6 percent, calling them the florin and genovino, respectively. They became so popular that Venice in 1284 adopted the florin, calling it a ducat, initially with a weight of 3.545 grams and a gold purity of 99.47 percent. The term ducat came to mean a trade coin of 3.5 grams gross weight 98.6 percent pure gold. Ducats traded widely across Europe and the Middle East and were also struck in the Netherlands.

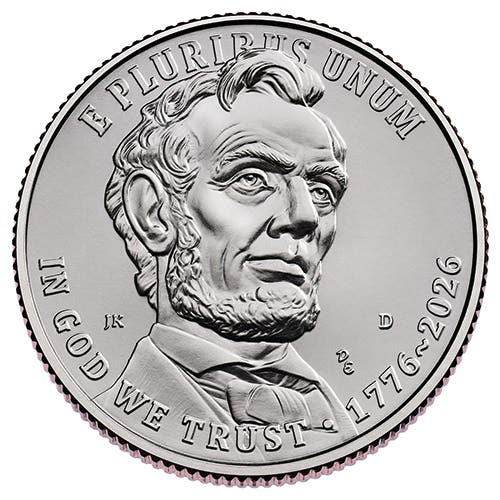

In the Western Hemisphere, the Spanish 8 reales became the dominant trade coin. It was even so popular that the former British colonies that became the United States of America established the weight of its silver dollar to match the weight of the average 8 reales (later called a peso). When the Canadian Confederation was formed in 1867, it also adopted the dollar denomination with a value for many decades at par with the U.S. dollar.

The Latin Monetary Union (LMU) was formed by France, Belgium, Italy and Switzerland in 1865 to issue coinage matching the standards of French coins and using the French gold/silver ratio of 15.5/1. Greece joined the LMU in 1867. Spain and Romania did not join the LMU but did strike gold coins of the same gold content as the 10 and 20 francs coins. The Austro-Hungarian Empire did not join the LMU but did issue its own gold coinage of dual denominations of 4 florins/10 francs and 8 florins/20 francs to match LMU standards. Several countries in eastern Europe and a few in South America also adopted LMU coin standards before the LMU disbanded in 1927.

After World War II, the U.S. dollar was the only major currency readily convertible by central banks into gold (until August 1971) at a fixed rate of $35 US per troy ounce of gold. This resulted in the U.S. dollar effectively becoming a world currency, where up to 90 percent of all international commerce was priced and paid in U.S. dollars. With economic growth around the world in recent decades, the use of the U.S. dollar in international commerce has fallen to 60 percent of the total, and continues to decline.

The U.S. dollar is widely accepted in everyday commerce across most of the Caribbean nations. It is also used as legal tender in several nations and current and former U.S. territories, including American Samoa, Bonaire, British Virgin Islands, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guam, Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Panama, Puerto Rico, Timor-Leste, Turks & Caicos, U.S. Virgin Islands and Zimbabwe.

To match the efficiencies of using a matching monetary system, the European Union created the virtual euro denomination on Jan. 1, 1999, and began circulating coins and currency in 2002. The euro has now displaced 19 national currencies in Europe and is accepted in some other countries.

The effort to create matching monetary systems was almost always spurred by the private sector desire to promote commerce.

There are proponents of a single world monetary system. That might sound attractive, in theory. But, the implementation of such a system would deprive national governments of significant autonomy – the ability to set their respective budgets and influence their individual economies. Most of the matching monetary systems throughout history developed on a voluntary basis. It is unlikely that any global monetary system could be proposed that would receive unanimous approval by the world’s governments.

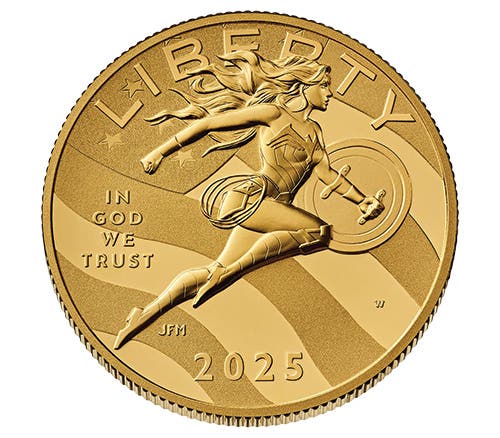

Patrick A. Heller was honored as a 2019 FUN Numismatic Ambassador. He is also the recipient of the American Numismatic Association 2018 Glenn Smedley Memorial Service Award, 2017 Exemplary Service Award, 2012 Harry Forman National Dealer of the Year Award and 2008 Presidential Award. Over the years, he has also been honored by the Numismatic Literary Guild (including twice in 2020), Professional Numismatists Guild, Industry Council for Tangible Assets and the Michigan State Numismatic Society. He is the communications officer of Liberty Coin Service in Lansing, Mich., and writes Liberty’s Outlook, a monthly newsletter on rare coins and precious metals subjects. Past newsletter issues can be viewed at www.libertycoinservice.com. Some of his radio commentaries titled “Things You ‘Know’ That Just Aren’t So, And Important News You Need To Know” can be heard at 8:45 a.m. Wednesday and Friday mornings on 1320-AM WILS in Lansing (which streams live and becomes part of the audio archives posted at www.1320wils.com).